Your work centers refugees, refugee camps, and foreign humanitarian aid. How does the history of displacement and aid in Eastern Europe relate to and differ from other contexts? What does the historical record help us understand about these subjects in their contemporary manifestations?

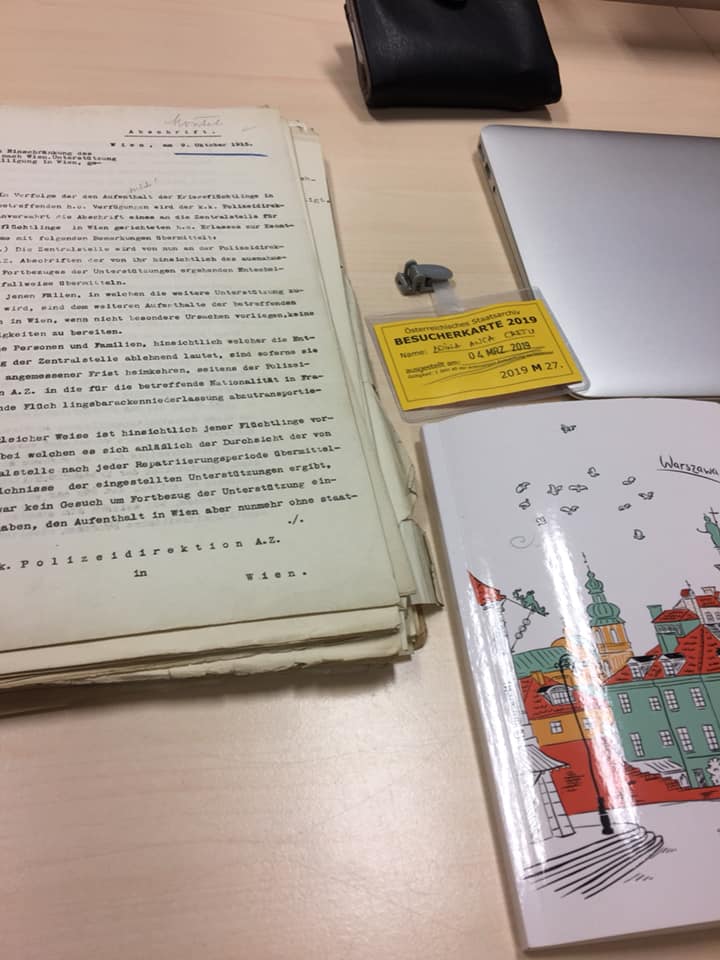

In my work, I like to think in more relational terms; namely, I like to think through the history of displacement and foreign aid in Eastern Europe in relation to histories of other contexts. I am cautious about highlighting exceptionality in general and rather prefer to highlight the ways actors in Eastern Europe shaped trajectories of foreign aid and/or addressed displacement in contexts of war, in particular, and what this means for broader histories of refugees, for instance. More specifically, in my forthcoming book, Foreign Aid and State Building in Interwar Romania: In Quest of an Ideal (Stanford University Press, 2024), I look at the ways various Romanian state builders established their own rapport with foreign aid organizations in a period of transformation in the interwar period. The current iteration of my second project is related to the development of modern refugee encampments. I place this narrative in the context of the First World War and in Austria-Hungary. This proposes a re-thinking of chronologies in terms of the history of refugee policy more broadly. In this context, I interpret the history of displacement and of aid in Eastern Europe as important pillars in the broader understanding of humanitarianism, development, refugee movements and their “management.”

Indeed, these are two historical topics with contemporary echoes. If we look at the ways I approach the history of foreign aid in Eastern Europe—namely, primarily in terms of the ways recipient actors determined humanitarian and proto-developmental processes in the interwar period—it can be argued that this is an instance of a historical record that sheds light on the ways international and non-governmental organizations could strengthen local structures of power. By contrast, in my view it is vital to understand mechanisms of responses to issues of displacement in their particular context. While this has become a topic that lends itself to transhistorical analyses, I am cautious about drawing broad conclusions that relate the landscape of refugee policy in the First World War in a moribund Austro-Hungarian monarchy to current border policies, for instance. I seek to understand the geneses of refugee containment and assistance mechanisms and propose an opening of discussion and future projects that compare or build on this particular historical record.

What does it mean to think internationally in area studies? How would you characterize our field’s overall engagement with how international forces have shaped Eastern Europe – and what new trends are emerging? What can these trends tell us about the future of area studies?

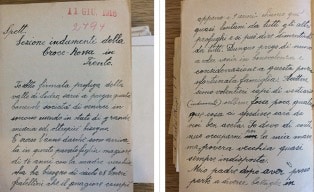

In my own work, I try to use different angles of reading what can be called “national histories.” “Thinking internationally” certainly has a content component: the inclusion of Eastern European narratives and actors in international history. However, it also has a methodological component: I believe that there is value in exploring archives outside national boundaries and putting them in conversation with local and domestic stories. For example, my book uses material from archives of the American Red Cross, the American Relief Administration, and the Rockefeller Foundation, which, in turn, gives new insights in terms of how various political leaders, but also experts or architects of a burgeoning civil society, conceptualized and shaped meanings of state building in the interwar period.

Historians of the region have started to look at Eastern Europe in an “anti-periphery” way.

We are in an exciting moment for our field because various historians of the region have started to look at Eastern Europe in an “anti-periphery” way (if I may describe it as such). Yes, different voices have previously alerted us to the need to halt our thinking of the region as passive and backward. However, at this point, we really see historians shedding light on the ways Eastern European actors shaped, interacted, or adapted so-called international forces and their potential influences themselves. For example, there is excellent work emerging on the ways Eastern European experts shaped aspects of global governance via the League of Nations or, later on, the United Nations. So, in this sense, I believe that we are in an exciting moment of area studies, as historians are more focused on exploring Eastern Europe in terms of transnational relationships and networks and, in this way, they shed light on how this region and its actors have actively become part of various global processes.

How would you describe the position of Austria-Hungary as a subject of analysis within the larger field of SEEES? To what extent does an area studies framework either lend itself to or obfuscate the study of this subject?

I arrived to the study of Austria-Hungary from outside, so-to-speak. I had studied the region and European history in the aftermath of the demise of the monarchy. However, I have been very lucky to come into a burgeoning field of research, as historians are shifting from thinking of 1918—the year of the collapse of the monarchy—only through the lens of the fractures that it led to. There is now new thinking on how facets of the monarchy and its governance were embedded in post-imperial nation-state making, as well as everyday lives. So, in this sense, understanding Austria-Hungary with all its convoluted bureaucracies, legislation, and issues of nationalism and national indifference, is becoming vital to understanding state- and nation-building in SEEES. But I would even say that the state of the field on Austria-Hungary has implications for understanding European history or the history of empires more broadly. These are two fields that somehow (and I would even say ironically) have found relatively little space for Austria-Hungary as object of analysis, as the study of the monarchy has arguably remained in its own contained historiographical microcosm. This is something I try to engage with in my own work on refugees in Austria-Hungary during the First World War: I shed light on this story not merely as one of a frail monarchy, but also as a bigger story of Europe and its refugees.

How do you approach teaching courses in Modern European History? What advantages might a historian of Eastern Europe have in this regard and what challenges might they face?

I have primarily taught history of migration, history of refugees, and history of humanitarianism, focusing on the European context. So, in this sense, I approach it from both a chronological and thematic perspective. I follow a couple of conventional starting points as I focus on narratives surrounding the emergence of the International Committee of the Red Cross via Geneva-based men of influence in the nineteenth century or on the First World War and the making of the modern refugee in that era. Eastern Europe has been a space of production of refugees in times of war or during repressive regimes; it has also been a space of attention for Western humanitarian actors in different moments in time due to war destruction and natural disasters, but also due to inherent beliefs that this is a region that could be improved. This was certainly the case in the interwar period, the moment I have studied most. Therefore, in my view, any history of refugees, of migration, of aid in the European context cannot be disentangled from the history of Eastern Europe. This is the true advantage of being an expert on this region and its countries.

The challenge I have identified thus far is more related to the practice of teaching and students’ background and baggage. In certain situations, I have been told and have observed that students have relatively limited knowledge of Eastern European history. Placing a story of migration in an easily transmitted context has been a structural challenge given that the history of Eastern Europe has been sidelined outside the countries of the region. While this might be a cliché from a research standpoint, we are still seeing teaching and courses that extricate Eastern European history from European history more broadly. This truly remains a challenge in our field, in my view.

How have contemporary events, including refugee movements, shaped your research? How have you seen these events shape historical research on refugees more broadly?

Early September 2015 was an important moment in my view. Then, a photograph of the lifeless body of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi lying face-down on a Turkish beach near Bodrum, made the rounds in traditional and social media. However, it also started to dominate historians’ own approaches to how to study refugees and humanitarians. Historians reacted to Alan Kurdi’s tragic end and its visual, writing studies on humanitarian photography, refugees’ victimhood, and aspects of solidarity with their plights with a historical perspective. That was a moment that, in my view, marked a shift in historians’ attempts to explore the experience, albeit a deeply tragic one, of the (universal) refugee.

Historical empathy is not easy to address and navigate, particularly when exposed to issues of trauma and suffering; the sources I look at, especially first-person documents, carry these themes rather prominently. On a personal level, in early 2022, I found myself watching countless news reports about Ukrainians fleeing their invaded country, images of children crying as they left their fathers and their homes. It was about then that I realized that my work needed to involve refugees’ experiences and their voices (even if in different registers); while, as I mentioned before, I caution against imperfect comparisons between current border regimes and past refugee policies, I can also say that, in many ways, observing contemporary experiences of forcefully displaced people motivated an empathetic response that drove a closeness to my historical subjects.

Doina Anca Cretu is a historian of foreign aid and migration. Her work is at the intersection between international history and modern history of central and eastern Europe. She is currently a Research Fellow within the ERC Consolidator Grant “Unlikely Refuge? Refugees and Citizens in East-Central Europe during the Twentieth Century” (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague) and a Visiting Lecturer at the University of Vienna. Anca holds a PhD from the Graduate Institute, Geneva; she was a Max Weber Fellow at the European University Institute in Florence, as well as a Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford, the Graduate Center at the City University of New York, and at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. In September 2024, she will start a new position as Assistant Professor of Modern European History at the University of Warwick (UK). Her first book, Foreign Aid and State Building in Interwar Romania: In Quest of an Ideal, will be out later this year with Stanford University Press.