Following Russia’s escalation against Ukraine in late February 2022, Moldova accommodated more Ukrainian refugees than any other European country, proportionally. This was reflected in one of Moldova’s self-promoted country mottos: “Small Country, Big Heart” [in Romanian: “Țară mică, inimă mare”]. The motto was devised by the ruling Party of Action and Solidarity [Partidul Acțiunii și Solidarității, PAS] of the incumbent president Maia Sandu. This might seem immodest to a foreigner visiting Moldova, but numerous statements by rank-and-file refugees and Ukrainian officials alike, including President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, speak for the fact that Ukraine is grateful for what Moldova did for the neighbouring country invaded by its Eastern Slavic not-anymore-brother. Even Transnistria, the breakaway Russian-controlled territory along the left bank of Dniester River, internationally recognized as belonging to Moldova, welcomed Ukrainian refugees. For a foreign observer, Transnistria being pro-Russian and welcoming Ukrainian refugees is confusing and incoherent. Indeed, to a certain extent, it is. But harboring pro-Russia sentiments and welcoming Ukrainian refugees in Transnistria is not a total contradiction. In 1992, during Russia’s war against Moldova, formally condemned only by Ukraine at that time, many Transnistrians found refuge in Ukraine. Today, they show their gratitude to the country that gave them a temporary shelter in dire times three decades ago.

The West has become more interested than ever before in Moldova’s current issues, its past, and its future.

The West as a whole, meanwhile, has become more interested than ever before in Moldova’s current issues, its past, and its future. International mass media and mainstream news channels and websites interview local and foreign experts on Moldova almost on a weekly basis. Western historians and other social scientists have visited Moldova quite often since the beginning of the war. In the last two years, more Western scholars from top-notch universities and renowned research centers have visited Moldova than in the 33 years since independence altogether. At least, that is the impression one gets from the vantage point of the archives. This is primarily because, once the war commenced, access to former Soviet archives dwindled dramatically. As the most important Soviet archives, located in Moscow and Kyiv, became difficult for international scholars to access after February 2022, many have looked increasingly to non-Russian and non-Ukrainian archives. While the Soviet archives in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia were a popular destination long before February 2022, now Moldova and, to a certain extent, Georgia and Armenia, have become important additions to the list.

Notably, a new policy toward archival access in Moldova had already been announced before the war started. That was a result of the historical victory of Maia Sandu in the 2020 presidential elections and, in the following year, of her party, PAS, in the parliamentary elections. For the first time in Moldova’s post-Soviet history, a party driven by clear-cut democratic and pro-Western values received 67 out of 101 legislative seats. The resulting government was the first to include the modernization of archives in its programs’ priorities. It also embarked on a new “memory policy” aimed at harmonizing interethnic relations and going beyond the deep divide—originating in the early 1990s—between the Romanian-speaking population (some identifying as Moldovans, others as Romanians) and the Russian-speaking minorities, including the Gagauz Turkish-speaking and Christian Orthodox communities in the south. PAS’ doctrine in bringing together Moldovan society is that no matter one’s ethnic, linguistic, or religious allegiance, everybody should be, first and foremost, loyal to the Moldovan state. In other words, having multiple identities is not a problem, as it is normal in the global age to have more than one—though one must choose one over the other when they are at odds with each other.

This has new resonance in the context of the war: those Russian-speakers who sympathize with Russia’s aggression against Ukraine seem to constitute a lethal threat to Moldova’s independence and its European future. Moldovan identity is viewed as a sum of manifold identities glued together by a shared official language, Romanian, and a familiarity with the basic facts of its national history, which is understood and conceptualized since 1990 as part of a history of Romanians (i.e., the space in which Romanian-speaking population are a majority). In contrast to claims by some, PAS’ doctrine on the identity issue is not a neo-Soviet doctrine justifying the existence of separate Romanian and Moldovan identities. The Soviets insisted the latter were antagonistic and irreconcilable, criminalizing Moldovans who identified as Romanians being criminalized and exiling them, first to Siberia during Stalin’s rule and after 1953, to psychiatric hospitals. PAS’ viewpoint, shared by more and more Moldovans, no matter their ethnic allegiance, is that there should be two states with Romanian-speaking majorities, Romania and Moldova, and that the trauma of the Soviet occupations of 1940 and 1944 could be resolved within the European Union, assuming that after Moldova joins the EU, state borders will become symbolic.

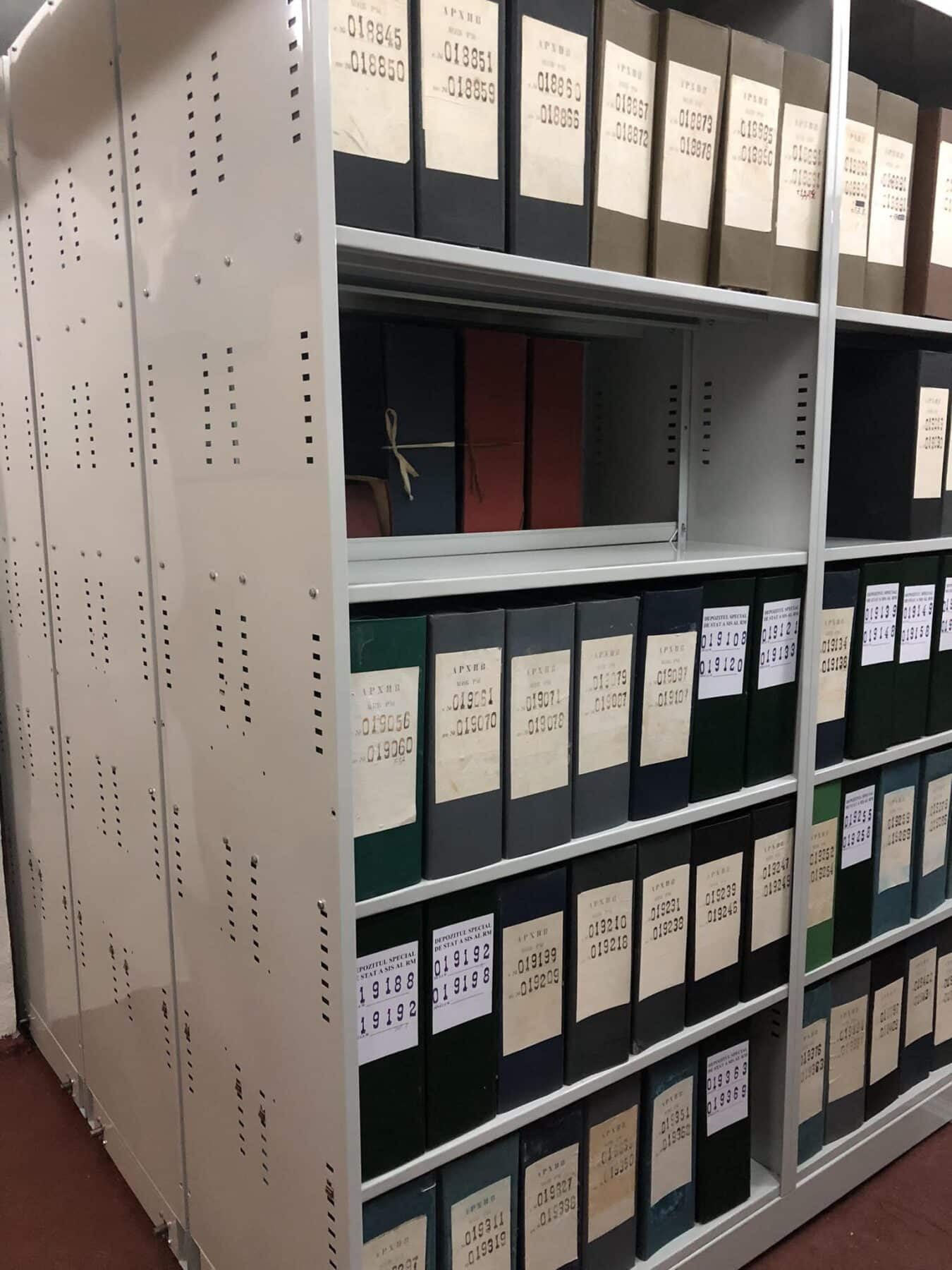

In the last few years, the national archives have received an important increase in terms of financial support from the government. This support went into modernizing its premises, improving the conditions in which files are preserved in its warehouses, using microclimate to buffer unstable conditions, and disinfecting files affected by various pathogens, but also digitizing the inventories and their uploading on the website of the state archives, run by the National Agency of Archives (Agenția Națională a Arhivelor, ANA). Though the name is misleading, the latter is the corresponding institution of the National Archives in the United States, France, UK, or Romania. At the moment, more than 5,000 inventories, of fonds spanning the Middle Ages to the post-Soviet period, are available online for download in searchable PDF format. Uploading the inventories online and increasing the visibility of what ANA is doing on social media and YouTube has contributed, among other efforts, to a rebranding of the Moldovan archives within Moldova, in the region, and worldwide. Due to these changes in access and digitization, and the impact of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, ANA has been visited by more researchers from abroad since 2022 than in the last three decades combined. For experienced scholars or junior ones in the advanced stages of their research, ANA has organized roundtables at the archives and guest lectures at the Faculty of History and Philosophy at the State University of Moldova. Among the guest lectures in the last half a year were those of Catriona Kelly (Cambridge, UK), Sophia Horowitz (Harvard), and Suzanne Freeman (MIT).

At ANA, one can corroborate Soviet claims about the Holocaust with Romanian records in the same reading room.

In the last two years, the archives have also digitized several important fonds, such as the list of people deported by the Soviets from the Moldavian SSR in 1949, which includes about 35,000 names, or around 99% of those deported. Another digitized fond is the one on the Sfatul Țării, the quasi-parliament of Bessarabia that voted for a union with Romania on March 27, 1918. This project was made possible by a grant from RoAid, the Romanian Agency for International Development, which allowed the archive to buy two high-resolution scanners. The other digitized fond is very important for the politics of memory in present-day Moldova. This is the list of victims—killed or condemned to the Gulag, all in all about 10,000 persons—of the Great Terror of 1937-1938 in the interwar Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within Soviet Ukraine, the territory on the left bank of the Dniester River that today harbours the pro-Russian secessionist regime.

ANA has documents spanning five centuries, covering the history of three empires (Ottoman, Tsarist, and Soviet) as well as documents from the Romanian interwar and WWII periods. Importantly, ANA holds both Soviet and Romanian documents on the Holocaust in Bessarabia and Transnistria. It is well-known how subjective Soviet sources are, especially ones on the activities of the political police, but also on the Holocaust perpetrated by the Antonescu regime in Bessarabia and Transnistria. One way to address this is to corroborate the Soviet claims with Romanian records that document, in detail, the mass killings and conditions of detention in ghettos and camps. At ANA, one can do that in the same reading room.

ANA holds 19,000 files on the victims of the Soviet repression, all transferred to the archives from 2010 to 2016. Last May, ANA signed a collaboration agreement with the Service of Intelligence and Security (Serviciul de Informații și Securitate, SIS), formerly the KGB of the Moldavian SSR. As a result, the transfer of files has resumed after having been discontinued 6 years ago due to political changes after Igor Dodon, a pro-Russia politician, became President in 2016. In less than a year, ANA received two batches of 2,200 files each. This year, Moldova will commemorate 75 years since the biggest Soviet mass deportation, which took place in 1949. On this occasion, ANA has worked out a plan with the government to expedite the process of transferring, through December 2024, all files related to political repression spanning the whole Soviet period. This amounts to about 100,000 files from the ex-KGB archives and the Ministry of the Interior. This is due to the support we have from President Maia Sandu, Prime Minister Dorin Recean, Speaker of the Parlaiment Igor Grosu, former Minister of Justice Sergiu Litvinenco and his ex-General Secretary Stela Ciobanu, and current Minister of Justice Veronica Mihailov-Moraru. This is all a part of an effort Moldova is making to distance itself from the Soviet past, denouncing CIS agreements, including on archival domain, and preparing to join the EU in the future. This is, to put it bluntly, a part of decolonization, and modest contribution to the worldwide process of de-centering Soviet history and giving voice and agency to non-Russian peoples.

Though ANA depositories are modest in comparison to Ukrainian and Russian ones, the collection holds a total of 1.6 million files in its warehouses. These fonds offer a small window into the Tsarist Empire’s varied policies, including but not limited to colonization, military build-up, policing the borderlands, pogroms, agricultural policy, and much more. As for Soviet history, due to Transnistria being part of Ukraine between the wars, the Moldovan archives—unlike the Baltic ones—hold files spanning the entire Soviet experiment, from 1917 to 1991. Thus, we have fonds on the NEP of the 1920s, the forced collectivization and Holodomor of the early 1930s, industrialization, policing the border with Romania in the interwar period along the Dniester River, the Great Terror, the cultural revolution, and many other subjects. ANA also invites foreign scholars who are doing research on the historical periods post-1940 and post-1953, as every document issued by Soviet state and party institutions, including the top-secret osobaya papka and personal files of nomenklatura, is declassified and accessible for photocopying. Foreign researchers can have their first order of 20 files in as little as one hour after their arrival, up to 20 files for each subsequent day, and are able to photocopy any file for a symbolic 50 USD cents per file (delo), no matter the number of pages per file.

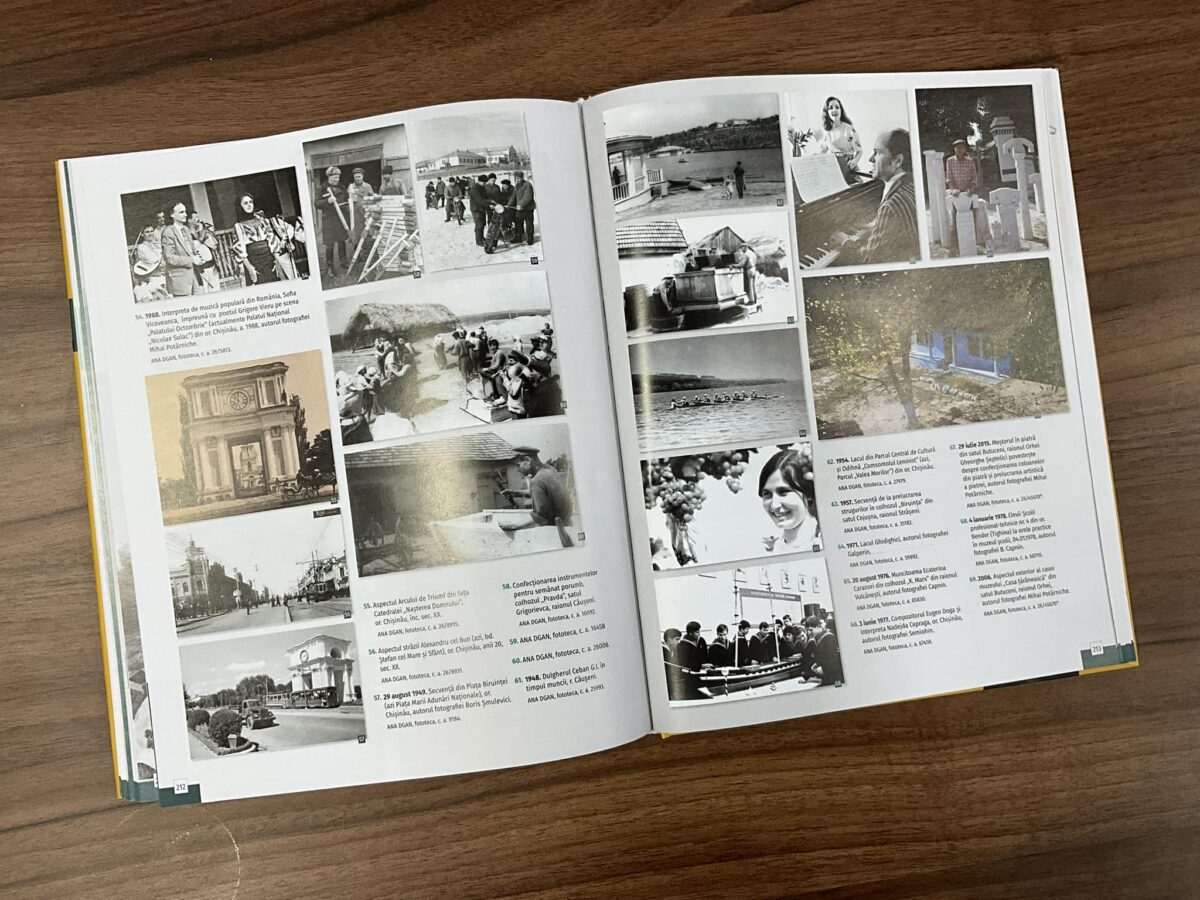

ANA also has a rich collection of pictures (250,000+) and a video collection spanning 1950 to 1991 (3,000+ videos, including animated, fiction, and documentary, 300+ of which are already posted on its YouTube channel). Last but not least, the identification of the files to be ordered can be done in advance by accessing the 5,000+ inventories posted online. For an overview of our fonds and collections, ANA advises scholars to consult the illustrated album (featuring an English introduction on how to use it) and a list of main fonds that can be accessed online using a QR-code.

Igor Cașu is the director of the National Agency for Archives of Moldova (since April 2022), and a Lecturer at the State University of Moldova, Chișinău (since 1998). In 2016, he was a Fulbright Scholar at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, giving talks on postwar famine at Toronto University, Yale, Harvard, and Stanford. He defended his Ph.D., on Soviet Nationalities Policy in the Moldavian SSR, 1944-89, at the University of Iași in Romania in 2000. In 2010, he was deputy chair of the Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Totalitarian Regime in Moldova. In 2014, he published, in Romanian, a book entitled The Class Enemy: Political Repressions, Violence and Resistance in Soviet Moldavia, 1924-56, based on party, KGB, and MVD archives. His recent publications include “The Benefits of Comparison: Famine in Kazakhstan in the Early 1930s in Soviet Context,” in Journal of Genocide Research, Volume 22, Issue 3, 2020; “Do Starving People Rebel? Hunger Riots as Bab’y Bunty in Spring 1946 Soviet Moldavia,” in New Europe College’s Yearbook (Bucharest), 2020; and “Police vs. Party? Institutional Hierarchies and Agency in Soviet Moldavia, 1944-1952,” in Contemporary European History, Volume 32, No. 1, 2022. He is working on a book on the postwar famine in Soviet Moldavia in the European context, 1946-1947.