Photography is both art and artifact. In the right context, can we not imagine a camera roll to be a living archive — uncurated, in some cases, chaotic in others, but with its contents created to capture passing moments as much as to engage in an aesthetic exercise? Roland Barthes opens his famous 1980 treatise on photography, Camera Lucida, observing, “One day, quite some time ago, I happened on a photograph of Napoleon’s youngest brother, Jerome, taken in 1852. And I realized then, with an amazement I have not been able to lessen since: ‘I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor’.” In a philosophical sense, every photographic portrait captures an historical actor. Landscape and architecture photographs, too, perform a similar function, documenting the sites that play witness to human history. Such photographs are exceptionally valuable for preserving, elucidating, and disentangling the layers of history of regions that, like Eastern Europe, have experienced profound destruction and demographic change since the invention of photography.

Lost sites of history can become ‘habitable’ again through photography’s fantasmatic journey.

The enjoyment and practice of photography, whether professional or amateur, whether on film or on a smartphone, can act as powerful artistic and psychic manifestations of historical thinking. my love for photography is a way of practicing my appreciation of history in daily life. In spring 2022, I lived in Wrocław, Poland completing dissertation research in regional archives. My research examines state and popular perceptions of Jewish belonging in Poland within the context of post-Stalinist migration. In the 1950s, the region of Lower Silesia was home to most of Poland’s remaining Jewish community. For most of its history, the capital and cultural center of Lower Silesia, Wrocław, was a German city known as Breslau before the region was transferred to Poland in 1945. The majority of Wrocław’s Old Town was destroyed in the Second World War, and German residents were expelled as Polish citizens migrated west and settled in Lower Silesia. My research subjects migrated to Lower Silesia in this period, and some smaller towns and cities, like Dzierżioniów, had significant Jewish populations of up to 25% in the period 1945-1950. Like many regions of Eastern Europe, Wrocław has long been a city of change and contradiction.

During my months of archival research, I spent my free time discovering Wrocław’s history and the beauty of Lower Silesia through my love of amateur urban and street photography. I spent hours exploring, seeking out sites of 1950s Jewish history, including community centers and private residences where my dissertation subjects lived. On some excursions, I tested out expired 35mm film. On others, I used my digital camera or even my smartphone. My photos of empty shop fronts and distracted passersby, perhaps lacking aesthetic significance and unlikely to garner attention from people on social media, deepened my appreciation for my historical subjects as I tried to mentally map the Wrocław I knew onto the lost city in which they lived. As in many cities and towns across Eastern Europe, the street names today are often different — ulica Stalina (Stalin Street) is now ulica Jedności Narodowej (National Unity Street), for example. In many cases, streets from the 1940s and 1950s have completely disappeared and do not map easily onto contemporary Wrocław, wiped out by postwar reconstruction and socialist urban planning. The city today is an urban palimpsest, greater than the sum of its rubble and new construction, its historical layers of changing linguistic, ethnic, and national contexts.

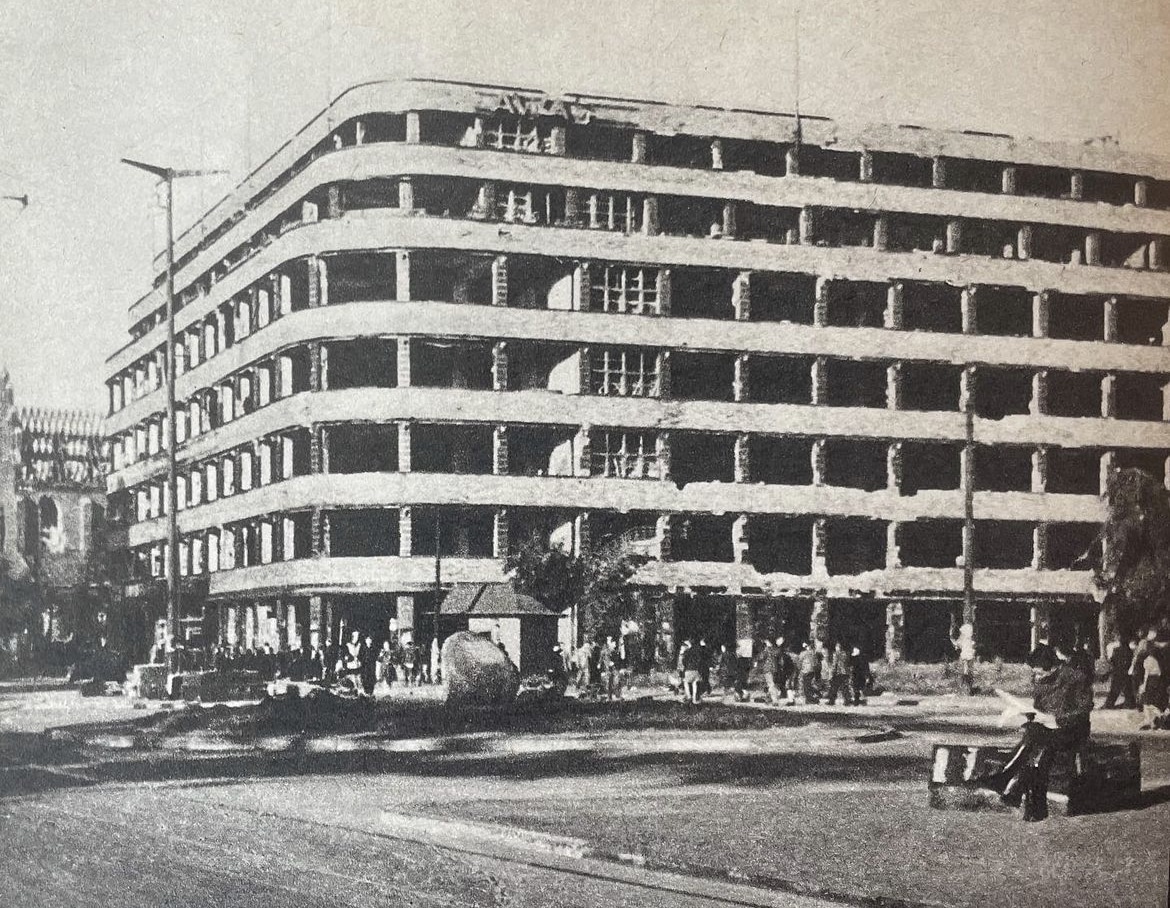

On a warm day in May, in an antykwarium (antique bookstore) near the university, I discovered an old copy of a photography book, Wrocław: wczoraj i dziś (Wrocław: Yesterday and Today), published in Poland in 1979. This book presents side-by-side photos of Wrocław taken immediately after the war alongside (then-contemporary) photos of city life captured in the 1970s. As a historian of the 1950s, a period of rapid industrialization and change in socialist Poland, I was captivated by the contrast between the two sets of photos. Though, for years, I had studied the aftermath of wartime loss in Poland and had seen images of the war’s material destruction, these photographs moved me in unexpected ways, in ways that typically only images of faces and people do. In dissecting what he believes to be the emotional core of photography, Barthes writes:

For me, photographs of landscape (urban or country) must be habitable, not visitable. This longing to inhabit, if I observe it clearly in myself, is neither oneiric (I do not dream of some extravagant site) nor empirical (I do not intend to buy a house according to the views of a real-estate agency); it is fantasmatic, deriving from a kind of second sight which seems to bear me forward to a utopian time, or to carry me back to somewhere in myself…Looking at these landscapes of predilection, it is as if I were certain of having been there or of going there.

These photos triggered this fantasmatic longing, a feeling of having “been” there, both physically and emotionally. The sites in these photographs are not “visitable”, they are lost, but they are, in a deeper sense, “habitable”. More than expressions of voyeuristic interest, these historical photographs not only represent memory and meaning but embody and evoke it, capturing a desire to return or recreate, encouraging projection of self, and inspiring a novel and kinetic understanding of place and time. That, then, is the fantasmatic appeal of emotionally effective landscape photographs.

I bought Wrocław: wczoraj i dziś and decided to visit every location in order to recreate these photographs. I wanted to see if this artistic exercise could render any more legible the profound evolution of Wrocław’s postwar character. Through the resulting photograph sets, we can see the city’s overlapping heritages and the evolution of Wrocław’s architecture and identity, from initial reconstruction efforts, through socialist development, to contemporary growth. The photographs, when presented alongside one another as sets of three, are intended to propel you through the lens into the scene between the externalized utopian place of the contemporary images and the internal place “somewhere within yourself” triggered by the postwar photos. Through this exercise, lost sites of Eastern European history can become “habitable” again through photography’s fantasmatic journey. This meeting of art and history can serve as a pedagogical tool, as a work of photojournalism, but also as a fantasmatic journey through past, place, and self.

For this project, I took all photos with a Fuji X100S digital camera. Despite its limiting fixed 23mm pancake lens, this camera is very well-suited to travel and street photography. Because the lens is fixed, the user is forced to interact with the space more intentionally, to move closer to the subject, to accept the imperfect framing and ratios of certain shots. The photographers’ manipulation and setting of the shot must come from their own physical engagement with the subject — you cannot zoom in or out. This is a poor choice for portrait photography, but for my purposes an excellent tool for reflecting on the subjectivity of the photographical subject and the historical context of the cityscape.

The first stop on my journey was Wrocław’s bustling center, the main Market Square. Wroclaw’s Market Square is one of the largest in Europe, and the square’s construction dates to the early thirteenth century. The heart of the city, Wrocław’s Market Square is home to some of the region’s grandest examples of gothic German architecture, including its Old Town Hall (ratusz, Rathaus). Today it is home to museums, cafes, and restaurants (including a McDonald’s and a Hard Rock Café). In the summer the square embodies a classic European atmosphere, with buskers performing pop hits and tented patios giving shelter to people drinking Żywiec and Aperol.

Standing in this space, I felt connected to these two other female photographers who had in the 1940s and 1970s photographed the same – yet radically different— view. This revealed even more layers of the expansive Wroclavian palimpsest, layers of three women photographers through time, layers of the development and interaction of film and digital photography, layers of the evolution of the subjects of the images themselves.

Through these photographs, in the words of Barthes we are “looking at eyes” — or, in this case, urban landscapes — “that looked at” the catastrophes, challenges, hopes, and ambitions of the twentieth century in Poland. Yet what do we achieve by recreating these historical photographs? Do we get closer to an historical “truth,” if such a thing exists?

What about an emotional or existential one? In his 2001 novel, Austerlitz, examining post-Holocaust trauma and memory, W.G. Sebald conceives of photography as not only documentary in nature but as a site of temporal and psychic shock. The existential value of photography to Sebald — both generally and within the specific context of twentieth century “Central Europe” — is as an archive of nonlinear, frozen, brief traces of the painful historical past that supports and occasionally supplants the fallible, fractured, traumatized human memory. The photographs in this essay, when viewed individually, are largely documentarian in intention and tone. When viewed together, as sets of three, they take on Sebaldian features and “carry [us] back to somewhere within [ourselves].” Our eyes are drawn to the one building that stands recognizably in each photo of the Market Square. Our mind fills in the decades of socialist building and capitalist development that occurred in between each photo, resulting in the rush of trams and buses surrounding Renoma. We are moved by the loss we imagine to have preceded the oldest photo, and we return to the newest photos, again, to process this shock and see how our understanding of the present has changed for this vision of the traumatic historical past. Through this exercise, these photographs become an archive of the fantasmatic.

Photography can be a tool that allows people to process collective traumas and inscribe new meanings on a city’s history and identity.

It is because of these emotional reverberations, perhaps, that fantasmatic longing, that urban photography has emerged at the center of contemporary attempts to de- and re-construct the layers of the historical palimpsest that is postwar Wrocław. Technology has radically democratized photography as a hobby, and there are Facebook groups and meet-ups in Wrocław dedicated not only to urban exploration — a term referring to the hobby of exploring and photographing abandoned or forgotten manmade structures – but also to photographing and preserving remnants of Wrocław’s German and Jewish pasts, including German or Yiddish words painted on buildings. A community project organized by the Karpowicz Foundation, entitled “Spod tynku patrzy Breslau” (“Breslau from beneath the plaster”), focuses on photographing traces of Wrocław’s German past. In these groups, people share their own photos capturing pieces of Wrocław’s architecture, the captions reflecting not only the known historical background of the photos, but the photographers’ own memories of the place, their own reasoning for finding the place and photograph valuable. Multiple people will share photographs of the same sites, yet each photograph presents a unique perspective. Photography can be a tool not only of preservation and documentation but of agency and creation, of emotional engagement, a tool that allows people to process collective traumas and inscribe new meanings on a city’s history and identity. And there are countless new meanings to be found in the layers of Wrocław’s past — in traces of history hidden in flowering courtyards and fading signage just waiting for those willing to look.

Editor’s Note: Historical photos are sourced from Ignacy Rutkiewicz, Wrocław: wczoraj i dziś (Warszawa: Interpress, 1979.) According to the Article 3 of copyright law of March 29, 1926 of the Republic of Poland and Article 2 of copyright law of July 10, 1952 of the People’s Republic of Poland, all photographs by Polish photographers (or published for the first time in Poland or simultaneously in Poland and abroad) published without a clear copyright notice before the law was changed on May 23, 1994 are assumed to be in the public domain in Poland.

Frankee Lyons is a PhD candidate in Modern Eastern European History at the University of Illinois Chicago. Her research examines perceptions of Jewish belonging in post-Stalinist Poland, focusing on migration policies generated during and after the Polish Thaw from 1953 to the early 1960s. Lyons has taught for the University of Illinois Chicago and YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, and she served as a historical consultant for the Programs on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Lyons’ research has been supported by the U.S. Fulbright Program, Title VIII Grant Program, Auschwitz Jewish Center, the JDC Archives, and the Kościuszko Foundation. She was co-lead for the project Migrating Memoryscapes: Creating Community for Ukrainian Refugees Through Art and its resulting exhibition in Kraków, Poland. Her writing on the intersection of history and photography can be found in Peripheral Histories and Panorama: The Journal of Travel, Place, and Nature. Currently based in Warsaw, Poland, Lyons is reachable on Twitter and Instagram at @voyagehistory.