ASEEES thanks Margaret H. Beissinger, Princeton University, for chairing the prize committee and formulating the interview questions.

What motivated this book project? How did your book project develop from the previous work you had done on post-communist Poland?

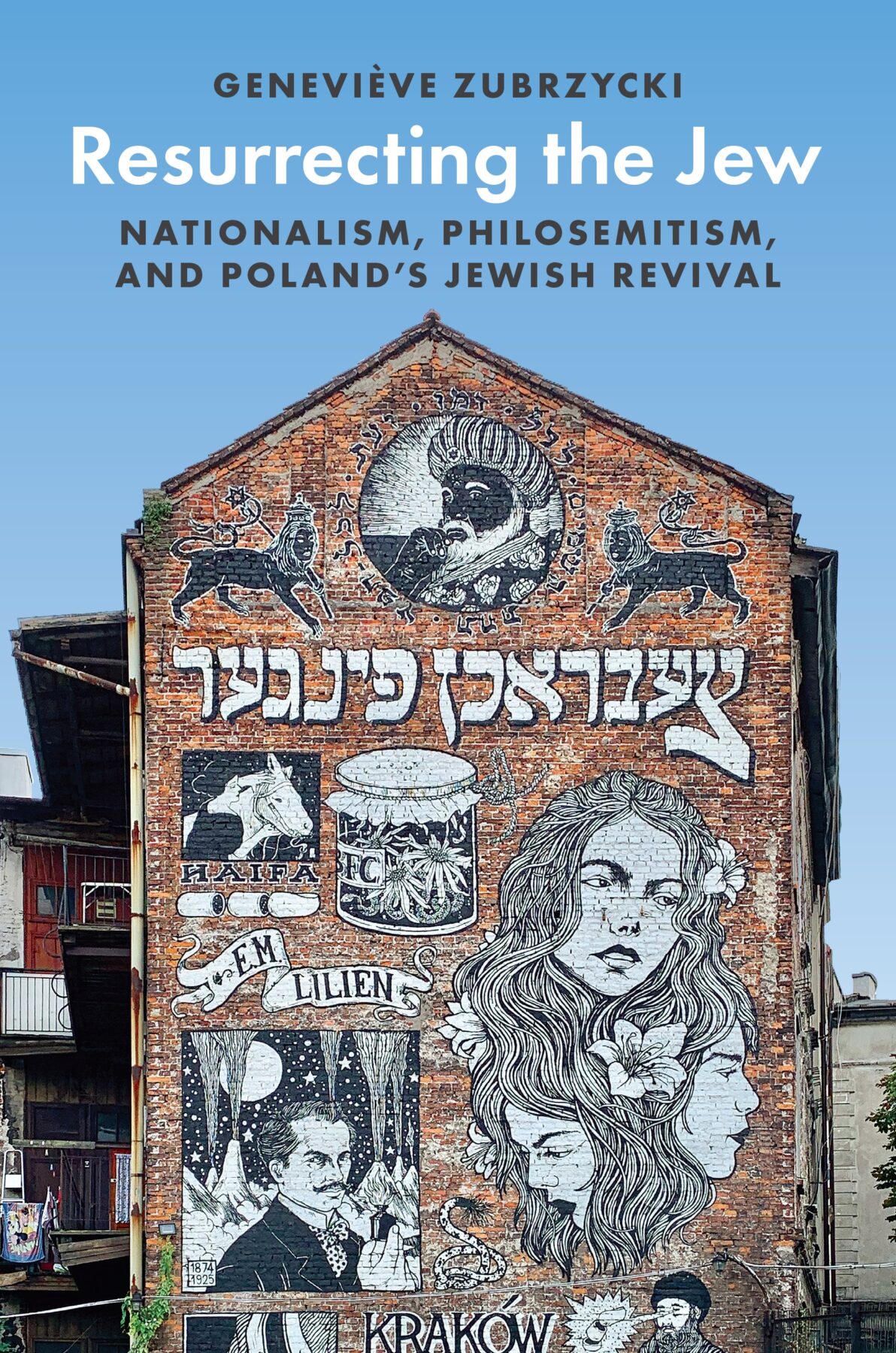

Resurrecting the Jew is a companion book to The Crosses of Auschwitz (University of Chicago Press, 2006). In that first book, I analyzed of role of Catholicism and antisemitism in symbolic boundary-making processes in Poland through an examination of memory wars about (and at) Auschwitz. In the five years separating the moment when I completed the research for Crosses and 2010, when I began the research for this new book, something spectacular happened: the preoccupation with Poland’s Jewish past and the interest in Jewish culture, which until then was the domain of a small group of urban cosmopolitan activists and intellectuals, had gone more or less mainstream. That phenomenon preceded Poland’s sharp turn to the right with the coming to power of the Law and Justice party, and thus could not be explained as a reaction to far-right populism. How to explain it, then?

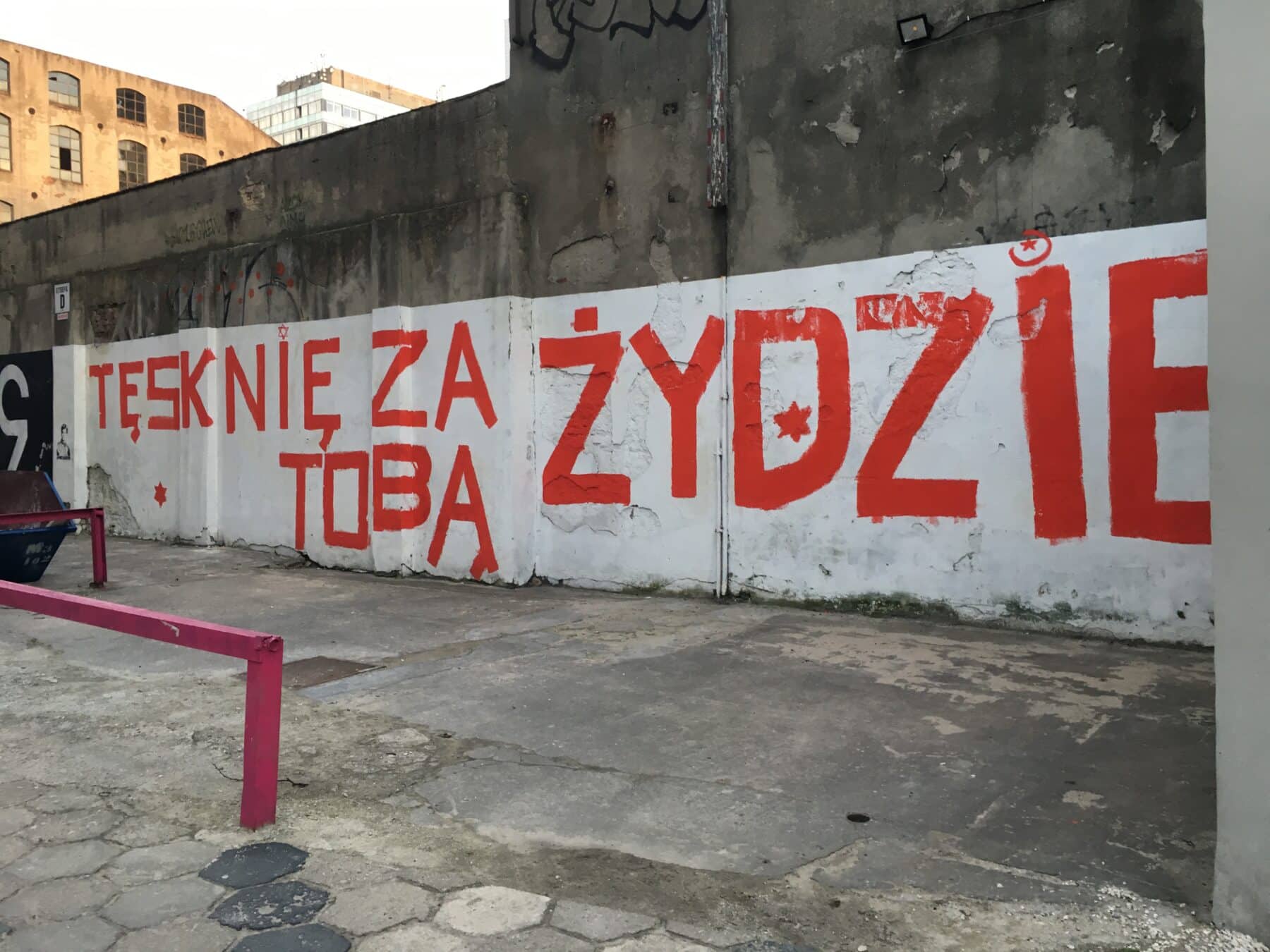

The phenomenon is undoubtedly related to ongoing memory wars about Poles’ role in the Holocaust, which have animated Polish public life since 2000 with the publication of Jan Gross’s Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (first published in Polish as Sąsiedzi: Historia zagłady żydowskiego miasteczka). It is also connected to the country’s accession to the EU in 2004. But I felt that there was more at work than the historical-political context. In Resurrecting the Jew’s very first pages, I assert that both anti- and philo-semitism in Poland are related to the structure of Polish national identity and its fusion with Catholicism, and that the resurrection of Jewish culture is part of an attempt by progressive Poles to secularize Polishness. The book then focuses, through visual analysis, participant observation, and over 100 interviews with Jewish and non-Jewish actors in the revival, on the various motivations of producers and consumers of a wide range of Jewish-related cultural products. I dig to uncover the many different significations Jewishness has for them. That interpretive approach is important if we are to make sense of the phenomenon and evaluate its significance.

How does Resurrecting the Jew inform and perhaps shift our understanding of 21st-century Poland?

While Poland might look like it is still very Catholic, Polish society has slowly but steadily been secularizing in the past 30 years. Polish sociologists of religion call this “creeping secularization.” But the process is picking up speed, and my analysis of the Jewish revival and Polish philosemitism shows why and how this is happening. The secularization of society does not simply happen via religious exit — people stopping to go to church or to baptize their children, for example. It also happens through the articulation of different idioms of national identity. The resurrection of Jewish culture by non-Jewish Poles is part of their effort to divorce Polishness from Catholicism; supporting the renewal of Jewish communal life is also a means to break the Catholic Church’s monopoly over society. So, the book points to important ongoing changes in Poland.

Polish society has slowly but steadily been secularizing in the past 30 years. My analysis of the Jewish revival and Polish philosemitism shows why and how this is happening.

How has Resurrecting the Jew been received in Poland?

Pretty well so far! I was invited to give several lectures at universities as well as at Jewish and Jewish-related organizations. A couple magazines wrote brief reviews. People appreciate my historical contextualization and my analysis of the phenomenon; I’m often told that the connections I establish between Polish progressive nationalism and the Jewish revival were surprising but convincing. That they had not realized the depth and different layers of Polish philosemitism, nor its relation to antisemitism and the structure of Polish ethnic nationalism. To have Poles — Jewish and non-Jewish, involved in the revival or not — find the book relevant and convincing is most rewarding. The book has also sparked interest in Israel. Haaretz and the Times of Israel reviewed it. The piece in Haaretz actually appeared on its front page! That says something about Israelis’ interest in Polish affairs.

What surprised you the most during the research stage of this project?

The social and geographic reach of Poles’ interest in all things Jewish. That interest was certainly more marked in liberal and urban circles, but it was not limited to those. I met a lot of activists from small towns and rural areas; many were practicing Catholics, and although some were motivated by the so-called exotic appeal of Jewishness, many were deeply engaged in a critical reflection about the connection between Polishness and Catholicism, about antisemitism, and were eager to build a more open polity.

How did the numerous interviews that you undertook with both Jewish and non-Jewish Poles shape your understanding of the grassroots nature of the Jewish revival in Poland today?

From outside and afar, Poles’ interest in things Jewish may seem opportunistic and even macabre. The commodification of Jewish culture and Holocaust tourism certainly play a role in Poland’s “Jewish revival,” but dismissing the entire phenomenon as merely commercial, and qualifying revitalized Jewish neighborhoods as “Disneylands” is obscuring rather than shedding light on the phenomenon. It was important for me to understand the motivations of non-Jews participating in the revival, as well as how Jews understood and felt about that participation. So ethnographic research was key for this project. I had to get close to the spaces and people where the revival is taking place. I conducted participant observation for 10 years, interviewing individuals several times during that period and getting to know them in different spheres of their lives. Many graduated, got married, had children; some emigrated, others retired. Being present at different moments in my interviewees’ lives was also important to allow me to see the phenomenon from within, and as it evolved through time. The stories shared with me speak to that grassroots nature of Poland’s Jewish Revival. This is not to say that the Polish state is not invested nor involved in it, because it certainly is — and I discuss why and how in the book.

What do you hope will be the most lasting contributions from this book in the next decade or two?

I think Resurrecting the Jew will be useful for thinking about Polish nationalism, its relationship to Catholicism, and the role of cultural practices in redefining Polishness. Beyond a particular case, social scientists aim to provide broader lessons. I hope the book will continue to make a strong case for qualitative analysis to make sense of puzzling phenomena. And I hope readers will find my concept of the national sensorium useful for the analysis of other societies; that my reframing of cultural appropriation toward a typology of “registers of engagement” with the culture of the “Other” will likewise be fruitful for scholars working on other cases.

I hope the book will continue to make a strong case for qualitative analysis to make sense of puzzling phenomena.

What is next on your research agenda?

At the Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia at the University of Michigan, I’m leading a project in collaboration with a U.S.-Ukrainian NGO, The Reckoning Project: Ukraine Testifies. With a team of students, we analyze testimonies of victims and witnesses of war crimes collected by first responders and researchers on the ground, coding them for the TRP’s legal team to identify patterns of criminality and ultimately make recommendations to the ICC and Ukrainian courts. We are also building an archive of testimonies and digital memorial, in map form, which we will soon launch. We build the site to be user-friendly so that the materials collected could be used in the classroom. This is keeping me quite busy, but I’m slowly starting a new book project on the aesthetics of nationalism. While it will be a more conceptual and theoretical book, it will be grounded on many of the cases I know best: Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Canada, the U.S., and France.

Geneviève Zubrzycki is the William H. Sewell Collegiate Professor of Sociology at the University of Michigan, where she directs the Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia and the Copernicus Center for Polish Studies. She has published widely on nationalism and religion; collective memory and national mythology; and the contested place of religious symbols in the public sphere. She’s the author of the award-winning The Crosses of Auschwitz: Nationalism and Religion in Post-Communist Poland (Chicago 2006); Beheading the Saint: Nationalism, Religion and Secularism in Quebec (Chicago 2016); and Resurrecting the Jew: Nationalism, Philosemitism and Poland’s Jewish Revival (Princeton 2022).In 2021, Zubrzycki was the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship and was awarded the Bronislaw Malinowski Prize in the Social Sciences from the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America.