The full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 renewed calls to diversify post-Soviet studies. In the field of political science, there has also been renewed attention to studying Ukraine. There persists, however, a heavily Russia-centric approach in our field with even well-established and highly successful scholars being offered the advice that others will only be interested in work about Russia.

In this piece, I draw attention to our opportunity to better incorporate and promote the study of Ukraine in its own right and the multitude of easily accessible sources to do so. We should use this period of renewed attention and momentum to create meaningful long-term change. This article is yet another call—building on many calls dating back to the first convention of our association in 1964—to study the post-Soviet region by considering a much greater diversity of voices and experiences than our community has in the past.

I write from the perspective of a political scientist who does empirical research and who has focused on researching, writing, and teaching primarily about Russia since I started regularly traveling to the country as a foreigner in 2002. I also write from the perspective of someone who has shifted their research to focus on Ukraine since the full-scale invasion. Additionally, I use the term “post-Soviet” as a term of convenience to denote the 15 independent countries that were former Soviet republics while recognizing that “post-Soviet” is a problematic term that identifies countries with long histories by only a few decades with some arguing it also feeds a false Russian narrative.

We should use this period of renewed attention and momentum to create meaningful long-term change in Post-Soviet studies.

Many academics are bound by a stickiness to a particular niche area of expertise. There are good reasons for that. We develop hard-won expertise in particular areas and sub-fields of our own disciplines. Given the length of time some topics take to develop, a scholar may devote a decade or more to a particular project. Nonetheless, I would encourage all of us to think broadly about our academic interests and how we approach area studies. For those who specialize in post-Soviet politics, one might consider themselves an expert in Russian politics and be understandably reticent to claim expertise in the politics of any other post-Soviet country. I would encourage us all, however, to consider that we can learn new things and write about the broader region without making one country the center of all these studies. We can learn new perspectives, and even new languages, and consider alternatives to making a single country the starting point for understanding an entire diverse region.

Below, I address the importance of continuing to incorporate and build on the focus and inclusion of Ukrainian perspectives, scholars, and scholarship in the field of political science. I offer some specific suggestions and resources that can help make Ukrainian work more prominent in the field of political science. Although I focus on studying Ukraine in political science, I think these suggestions have broader application to other countries in the post-Soviet region and to other disciplines.

Political Science After the Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine

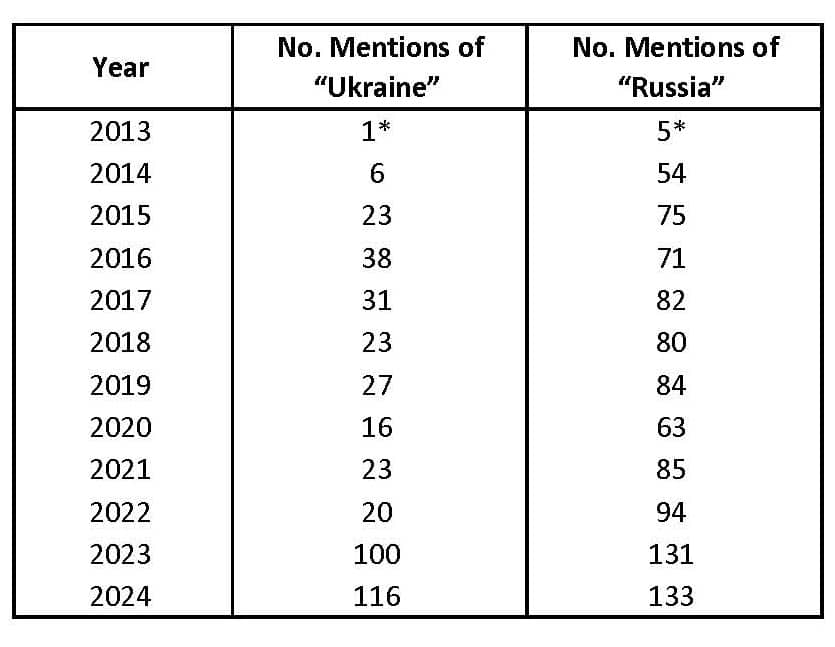

As in the broader academic community, in political science there was increased attention on Ukraine after the 2014 invasion and even more so after 2022. There was also, however, an increased attention to Russia. Below are the number of mentions of “Ukraine” and “Russia” in the programs for the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association from 2013-2024.

Mentions of “Ukraine” and “Russia” in the programs for the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA)

By this metric, the war in Ukraine significantly increased the study of Ukraine in political science while also increasing interest in Russia. In 2024, there are still fewer papers mentioning Ukraine than Russia, but the gap has significantly shrunk. The question is whether and how long this renewed attention on Ukraine will continue.

In practical terms, there is no quantifiable and correct amount of attention any given country deserves in the post-Soviet region. There is not, for instance, a magic correct number of panels that should be devoted to a given country at APSA. All countries are important. Furthermore, it makes sense that a war or other crisis would boost attention to a country within a discipline. I would argue, however, that we have an opportunity since the full-scale invasion in 2022 to more fundamentally rethink how we study the post-Soviet region and, in particular, to take the study of Ukraine more seriously in its own right. Rather than having the renewed study of Ukraine be a short-term blip, we can more seriously incorporate voices, theories, data, and perspectives that have long been overdue to receive more attention.

Other political science associations reflect the increased attention on Ukraine with increased coverage and panels dedicated to Ukrainian politics. For instance, at the 2024 conference of the Midwest Political Science Association (MPSA), I helped to organize a roundtable entitled “Research During Difficult Times.” The roundtable, which included Yoshiko Herrera, Volodymyr Kulyk, Lauren McCarthy, Silviya Nitsova, and Ivan Grek and was part of a workshop within the conference called “The Politics and Political Economy of Eurasia,” focused on a range of research challenges posed by the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the resulting expanded war.

Herrera noted that many of us have discretion in the content of our courses and encouraged us to exercise that freedom to choose different material. Kulyk and Nitsova noted the importance of including Ukrainian scholars in research collaborations. Academic work by Kulyk and Nitsova shows the value and importance of an empirical social science approach in studying Ukraine. Kulyk’s recent work explores Zelenskyy’s discourse before and after the full-scale invasion finding that Zelenskyy was able to creatively combine populism and inclusionary nationalism in his messages. Nitsova highlights the importance of understanding sub-national differences in elite strategies and civil society organizations in Ukraine, and the importance of understanding variation in how well local Ukrainian actors cooperate with international actors in pursuing domestic governance reforms.

Why More Voices May Produce Better Empirical Social Science Research

Many scholars of the post-Soviet region—with some notable exceptions—have an opportunity to learn from a collective failure to better predict and understand the full-scale invasion, Russia’s inability to quickly win the war, and Ukraine’s remarkable resilience. Some speculate that the Ukrainian government may have had a much better assessment of the likelihood of a Russian invasion and the poor conditions of the Russian military. At least part of this failure to anticipate such major events may have been an approach to area studies that undervalued Ukrainian intelligence sources and perspectives.

There are normative and scientific reasons to expand the perspectives, voices, and data that political scientists use. First, there is a compelling normative argument for decolonizing the study of Central and Eastern Europe, the Baltics, Central Asia, and the Caucuses. An under-appreciation of Russia’s imperial ambitions is at least part of the reason that some observers did not think a full-scale invasion was more likely. Others have made the case for de-centering the study of Russia and, by extension, post-Soviet studies. Juliet Johnson notes in her 2023 ASEEES presidential address that calls to de-center the study of Russia are not new and date back to the founding of the association in 1964 when a minority of scholars tried to push for a greater diversity of voices. Johnson further emphasizes that these are not calls to stop studying Russia nor, would I add, is there any real risk of that happening in the academic, security, or policy communities. As the largest and most powerful country in the region, there is often more funding and more interest in studying Russia than in studying the other countries of the region which are still often, though not always, incorrectly deemed too small to be of broader interest or importance.

There are normative and scientific reasons to expand the perspectives, voices, and data that political scientists use.

Second, there are practical and scientific reasons to better incorporate and focus on a variety of voices and perspectives from Ukraine. This may have been overlooked in the social sciences in part because the empirical social sciences often emphasize the need to develop testable hypotheses, collect data, and conduct analyses. Social scientists are often taught in graduate school about the dangers of being too biased by another culture’s perspective. Rather, social science training emphasizes the importance of testing generalizable ideas about how the world works. For social scientists conducting empirical research, however, expanding our networks and collaborating more with people from the place we are studying—especially if we ourselves are not from that place—helps us ask better questions, develop better theories, and collect more meaningful and accurate data.

One excellent example of how collaboration can produce better social science work is a contemporary history volume on Ukraine published in 2019 and edited by Mykhailo Minakov, Georgiy Kasianov, and Matthew Rojansky which was specifically designed to bring together experts who were based in the West and in Ukraine. The result is a volume offering remarkable insight into the recent political and social situation in Ukraine from prominent scholars. In addition to important theoretical contributions, this edited volume includes extensive empirical work presenting case studies, extensive survey work over time, and a better understanding of national identity in Ukraine.

Building a New Direction for Post-Soviet Political Science

What can we do to better study Ukraine in political science? To more permanently establish a shift in our study of post-Soviet politics, the general steps we can take are to teach, research, and collaborate more about Ukraine and with Ukrainian scholars and Ukrainian institutions.

Diversifying the scholarship we cite, the material we teach, and who we work with is easier today in the digital age. In political science, two popular websites are “Women Also Know Stuff” and “People of Color Also Know Stuff.” Both websites were created in reaction to those who said they would like to include more diverse voices, but either claimed there were not more diverse people to cite or that they could not find them. If someone is having trouble finding scholars from the region to include on a syllabus or to cite in a paper, the solution is likely to try a bit harder. Below, in the spirit of other efforts to diversify political science, I detail a variety of resources to help one do this.

In today’s digital world, there are a multitude of tools to help us find voices from the countries and places we study. There are online archives, academic blogs, the MAPA Digital Atlas of Ukraine and institutions like the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI) offering many resources remotely. We might sometimes hear the objection that there are not local voices published in the language of instruction, but with automated translation and other translation services readily available, this should not be a significant hurdle to assigning more diverse materials.

In the case of Ukraine, there is an abundance of excellent social science research about a wide variety of important topics, which is important for scholars in conducting their own research and in providing sources for teaching. VoxUkraine covers a wide variety of recent research on economics, society, governance, and policy reforms. The Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) provides a list of current publications (many in English) by its scholars. Datasets like the repository, “Building a Comprehensive Repository of Hromada-Level Data in Ukraine to Facilitate Research and Informed Policy Decisions,” developed by a research team at the Kyiv School of Economics, are publicly available. The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) regularly publishes survey results, often in English.

Other important work has also advanced our understanding of Ukrainian politics after 2022 and provides a rich source of resources to diversify how we study the post-Soviet region. Maria Popova and Oxana Shevel wrote Russia and Ukraine: Entangled Histories, Diverging States, a highly informative book for research which is also accessible for teaching at the undergraduate level. This book was published in 2024 and covers the post-communist period through the full-scale invasion. Their work is an invaluable work in paving the way forward in understanding post-Soviet politics. Olga Onuch’s work spearheading the research project, Determinants of ‘Mobilisation’ at Home & Abroad: Analysing the Micro-Foundations of Out-Migration & Mass Protest, includes multiple wartime surveys and an extensive list of recent publications. Olga Onuch and Henry Hale’s book, The Zelensky Effect, details the rise of Zelensky and his role in the development of Ukraine’s national identity. Arturas Rozenas and Alexandra Vlasenko show that the symbolic politics driving the destruction of Soviet monuments in Ukraine affects electoral behavior. These are, of course, recent examples and a small sampling of all the resources for studying Ukrainian politics. In short, there are many easily accessible resources for incorporating an understanding contemporary Ukrainian politics into one’s research and teaching.

We must also continue with renewed efforts—some of which were in place before 2022—to promote institutions and scholars from the region in the social sciences. KSE has partnered with universities around the world to create the Ukrainian Global University and is running a second round of its Virtual “Scholar in Residence Program” with the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Professional organizations like PONARS actively work to bring together scholars from the post-Soviet countries and those based in Europe and the United States. Since 2022, PONARS has increased its promotion of Ukrainian research with an excellent and regularly updated collection of short articles that can easily be assigned in undergraduate classes. ASEEES has promoted the inclusion of those living and studying in Eastern Europe and Eurasia with discounted memberships and some additional travel grants, and free membership for scholars and graduate students who are Ukrainian citizens residing in Ukraine or who have been displaced because of the war. You can donate to these ASEEES funds. These efforts are admirable and should be continued and expanded.

There are other ways to work with scholars, practitioners, and students in Ukraine which are of relatively low financial cost. For instance, Geoffrey Glenn (U.S. Peace Corps Virtual Service in Dubno, Ukraine), Olga Nikolska (with the NGO ISAR Ednannia in Kyiv), and Roman Oleksenko (a community project manager in Kyiv), and I have organized an ongoing speaker series held on Zoom focusing on Ukrainian resilience and civil society that began in September 2023. Our group of organizers has allowed us to find a connection between Western and Ukrainian perspectives and to link topics of academic and scholarly interest with the policy world. By design, our speakers have included 21 Ukrainians nearly all of whom are living and working in Ukraine today as well as a handful of other speakers with close ties to the country. Our attendees include policymakers, scholars, community members, and students. The topics have included a wide range of issues such as civil society in Ukraine, myths about Ukraine, women in war, kidnapped children, war from a teenage perspective, the impact of war on families and migration, diversity in Ukraine, and comedy during wartime. It would be easy to be skeptical about the value added of yet another remote speaker series, but we have strongly felt that our series offers something unique by amplifying Ukrainian voices and focusing on lived experiences and lessons learned about resilience and success for civil society.

The continued study of Ukraine is an easy case to make. When the war ends, there will be decades of reconstruction and development needed. Ukraine will continue to rely on foreign assistance in these endeavors. The generational cost of the war has been enormous, posing particularly tough challenges in rebuilding. In short, there are many policy and academic issues to study in Ukraine for a long time to come. The discipline of political science sits at the nexus of many of these important questions—many of which are related to issues of governance, national identity, and political economy—and, therefore, has an opportunity to lead the way in continuing to devote significant attention to Ukraine.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the resulting war have provided a chance to rethink how and why we conduct research. We should not waste this opportunity. Shortly after taking office in 2020, Zelenskyy explained in an interview that, “…people don’t really believe in words. Or rather, people believe in words only for a stretch of time. Then they start to look for action.” We do not want our acknowledgment that post-Soviet studies need revision to be merely words that are part of a short-term reaction to a crisis. We must work to take meaningful long-term action to de-center and diversify the study of the post-Soviet region, including taking seriously the study of Ukrainian politics in its own right. To paraphrase a current ad in Ukraine’s capital: Kyiv is waiting for us.

Sarah Wilson Sokhey is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Colorado Boulder, the founding director of Studio Lab for Undergrads, and a Faculty Associate at the Institute of Behavioral Science. Her research focuses on the interplay between politics and economics. Her book, The Political Economy of Pension Policy Reversal in Post-Communist Countries (Cambridge University Press, 2017) examines backtracking on social security reforms in the wake of the 2009 financial crisis and won the Ed A. Hewett Book Prize for outstanding publication on the political economy of Russia, Eurasia and/or Eastern Europe from ASEEES. Her current research focuses on the provision of public goods at the local level in Ukraine.