Omer Bartov

Professor of German Studies, Brown University

When did you first develop an interest in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies?

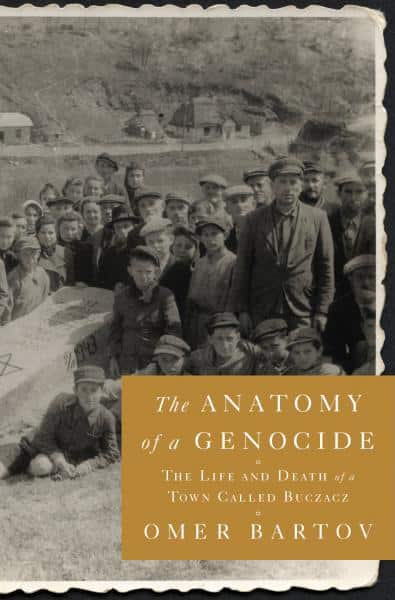

My interest in Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies coincided with my research on coexistence and violence in the town of Buczacz in today’s Western Ukraine. Initially I wanted to explore how a genocide such as the Holocaust occurs on the local level, when the perpetrators encounter their victims. I decided to pick a town in Eastern Europe, since that was where most of the Jews lived before World War II and where most of them were murdered. But as I studied the town I realized that I had to go much farther back in history in order to understand how an interethnic community, quite typical of many other towns in the vast swath of territory from the Baltics to the Balkans, had transformed into as community of genocide. That in turn meant that I had to spend many years studying the historiography and languages of the region and to understand its complexities and multiple competing narratives.

How have your interests changed since then?

Over the years since I began researching Anatomy of a Genocide my thinking has evolved from focusing only on the manner in which local violence is triggered by a combination of external forces and local dynamics to a fascination with how several narratives of origins and belonging can coexist side-by-side over centuries and why under certain conditions they develop antagonistic features which, especially at times of war and occupation, can facilitate fraternal violence of a particularly intimate and horrifying nature. In other words, I have become especially fascinated with the creative and destructive potentials of interethnic and inter-religious communities.

What is your current research/work project?

This has led me in turn to my current research, which entails coexistence and conflict in Israel-Palestine, to which hundreds of thousands of East European Jews moved in the twentieth century in order to create for themselves a national home, and where they encountered an indigenous population that viewed them increasingly as foreign European settlers and occupiers. Hence the dynamics that I traced in one part of the world were to some extent recreated in another, partly by the same protagonists and often using similar group and national narratives. This has also taken me on a personal journey from my mother’s hometown of Buczacz to my own homeland of Israel, and from an exploration of the erasure of Jewish life in Galicia to an investigation into the link between members of my own generation, both Jews and Arabs – born in Israel-Palestine shortly after the creation of the state and the ethnic cleansing of most of its Palestinian population – and the land which they call their home.

What do you value about your ASEEES membership?

Since I began my journey from modern Germany to Eastern Europe two decades ago I have encountered a multitude of scholars engaged in new and thriving areas of research, energized by the opening of hitherto sealed archives and by the ongoing struggles over the links between difficult pasts and threatening futures. This has greatly motivated me as well after years of engaging in German history and a growing sense that I had personally exhausted my interest in that region.

Besides your professional work, what other interests and/or hobbies do you enjoy?

I like learning new things, which is why I have been shifting my own geographical foci, and I feel that for me true engagement cannot be only professional, certainly not at the current time, but must also have a cultural, educational, and political dimension. This means that I maintain a strong interest in other forms of media that provide (at times quite pleasurable) insights into historical and contemporary issue, such as film and literature, and that I enjoy traveling to learn about new sites and cultures, and then enjoy learning about the places I have traveled to. Most of all, I like getting to know people.