Malte Rolf

Professor of Central and Eastern European History and Head of the Department of History, Carl von-Ossietzky-University of Oldenburg

When did you first develop an interest in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies?

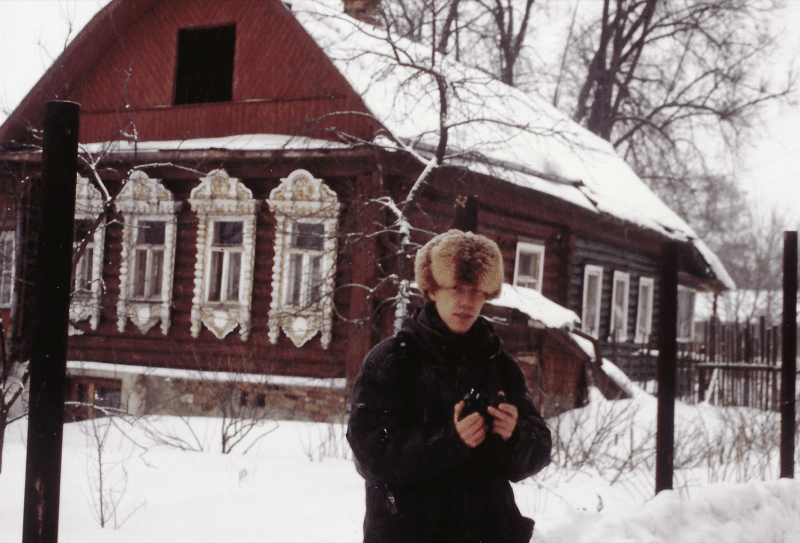

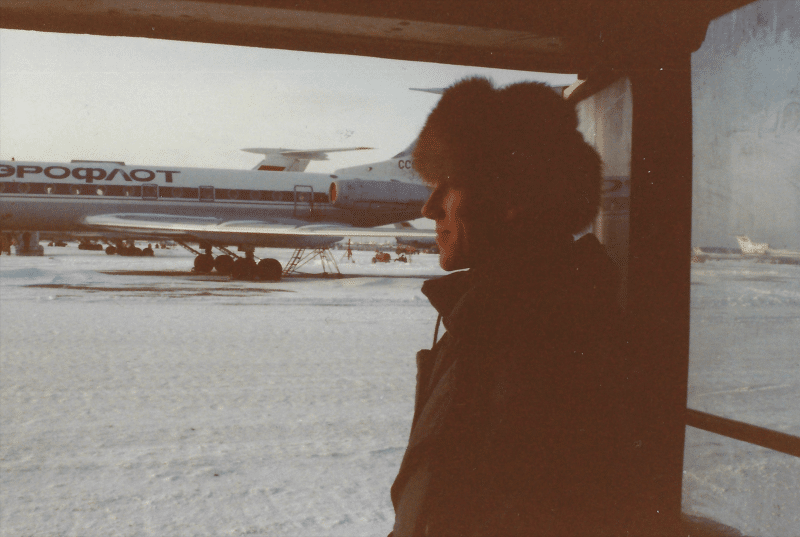

The point of no return though was my first trip to the Soviet Union in 1990. I spent four weeks in Moscow and fell in love with the country and its people. For me, coming from wealthy, well-organized, but boring West Germany it was an encounter with an exotic cosmos of a fundamentally different way of life, that was, at the same time, in the course of dramatic change. I witnessed openness to new ideas, a tremendous flexibility when it came to adapting to new circumstances, and an astonishing ability to extemporize in all fields of daily struggle. Being deeply impressed by this treasure chest of enigmas I still needed to resolve, I enrolled in Eastern European history courses right after my return from Moscow. Since then, I have spent almost four years living in various places in the former Soviet Union and Central Eastern Europe, I have traveled from the Baikal to the Balaton, from the Baltic states to the Balkans, and I have studied, lived, and conducted research in cities like Moscow, Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Warsaw, and Vilnius. East and East-Central Europe have become more familiar by now, but it has remained as fascinating to me as it was in 1990.

What support have you received throughout your career that has allowed you to advance your scholarship?

Along with some awards for my Ph.D. dissertation, I particularly profited from grants from the German research foundation. The DFG supported a series of research trips and long-term stays in Moscow, Petersburg, and Warsaw. I would also like to mention the award Humanities International that gave me the opportunity to have my Ph.D. dissertation translated into English and published in 2013 (Soviet Mass Festivals, University of Pittsburgh Press). With the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, I was able to present this book and my research at several institutions in the US. As for my follow-up project on imperial Russian rule, the Thyssen Foundation and the Volkswagen Foundation have enabled me to organize a series of international conferences.

What is your current research/work project?

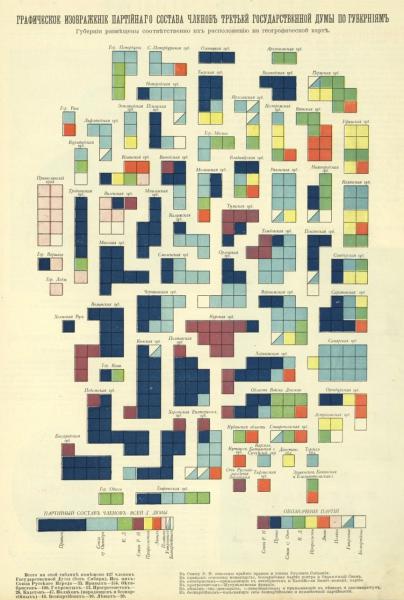

In collaboration with my colleague in Oldenburg, Philipp Schedl, I’m now dealing with Russian nationalists from the (Western) borderland regions of the Romanov Empire (1905-1914). With the Revolution of 1905, Russian nationalism as a political force gained strength. At the same time, Russian representatives of the okrainy – the borderland provinces of the Empire – became more influential in nationalists’ circles in St. Petersburg. e.g., they dominated the State Duma where Russian delegates from the border regions were highly over-represented. They were gathering under the slogan of “Russians of all borderlands, unit!”[1]

Local case studies have already depicted some of these nationalists’ circles in the imperial peripheries. We are now trying to investigate their overall impact on the political system in Russia before the First World War. Here, we hope to shed light on the political (self-)mobilization of Russian nationalists from the okraina-territories. We aim at exploring their rise within local Russian communities, their strategies of connecting trans-locally, and their influence on the political institutions of the imperial capital.

By doing so, our project opens new perspectives on the transformation of Russia’s political system. First, it portrays the leading players of local political mobilization and identifies their key notions of (Russian) national identity. Building on case studies of Warsaw and Kishinev – two centers of Russian okraina-nationalism – we inquire into practices of local community building and forms of political institutionalization in the borderlands.

Secondly, we elaborate on the initiatives of the radical right to connect trans-locally and to create distinctive okraina-organizations and pressure groups in St. Petersburg. How did borderland nationalists contribute to the political debates in the capital? What kind of strategies of agenda-setting did they develop? How influential were they in shaping the policy guidelines of the Tsarist government?

Thirdly, the project intends to explain why representatives from the Empire’s fringes succeed in dominating the heterogeneous milieu on the right-wing of Petersburg’s political scene. The rise of okraina-nationalists must be told as a story of tensions and frictions that in the end led to the “provincialization” of Russia’s political right.

Fourthly, we try to highlight those imperial images and semantics of nationalists that shaped the general political discourse in the late Romanov Empire. We explore how activists from the Empire’s margins managed to communicate an image of the peripheries as a homogenous okraina and how they reshaped and monopolized key contemporary slogans, e.g., the “Russian cause”.

To sum up: Our project examines the importance of okraina-activists in the context of an intensifying nationalization of the Empire after 1905. Taking a closer look at nationalists coming from the imperial fringes and exploring their imprint on the metropolitan political scenery also opens up comparative perspectives, as destabilizing dynamics of borderland radicalization can be traced as well in other large-scaled or colonial empires.

How has your involvement with ASEEES helped to further your career?

Most of all I appreciate going to the annual conventions. During my career, I have presented a large number of papers or have participated in round tables. Discussing my own research with a truly international audience has always been an outstanding experience for me and has deeply affected my research. I recall my first presentation in St. Louis in 1999 when I was just getting started with my dissertation project. Getting comments from someone like Richard Stites is something you’ll never forget. More recently, I have received tremendously valuable and stimulating feedback on my okrainy-nationalists-project.

Along with such intellectual input the conventions, of course, are wonderful places to establish international contacts. Over the years I developed close personal relations with many colleagues from the US and other countries abroad, some of which have turned into real friendships. And I’m sure that my books would have never been published in the US if it wasn’t for the chats at the booths of the ASEEES’ book exhibits.

As for my own career in Germany, I’m quite convinced that the international network I have at these ASEEES-conventions presented a significant benefit in the long process of applications and competitions.

Besides your professional work, what other interests and/or hobbies do you enjoy?

I do a little bit of sports here (hiking, biking) and a little bit of art there (currently, I’m involved in squeegee painting). But most importantly, we try to travel with the family as much as possible. This is the great thing about Europe: So many different cultures, languages, countries, and histories are so close by. There is much to discover in Central Eastern Europe.

[1] „Русские люди всех окраин, соединяйтесь!“ / „Russkie liudi vsekh okrain, soediniaites‘!“ in: Okrainy Rossii (1st of September 1907), p. 1.