You describe yourself as a “historian of citizenship and inequality in Soviet Eurasia” and have conducted research in eight countries of the former Soviet Union as well as in the United States. What about these subjects prompted you to pursue research in multiple countries?

Back in 2007–2008, I worked for a summer as an intern for Memorial Society’s Information and Research Centre in St. Petersburg before spending my full junior year abroad in Moscow and Berlin. Over the course of the year, I had the opportunity to travel broadly, both within provincial Russia—as far as the White Sea in the north, Astrakhan in the south, and Ekaterinburg to the east—as well as to Central Asia, the Baltic region, and Ukraine. My travels familiarized me not merely with the center of the former Soviet Union, but also its former “peripheries.” I was struck both by the profound differences and similarities of what I observed. In graduate school, I found that existing scholarship—after more than two decades of extensive work on nationalities policy—did much to explain differences across former Soviet space but was less satisfying on what united it. Of course, there were older answers focused primarily on oppression, but these told only part of the story.

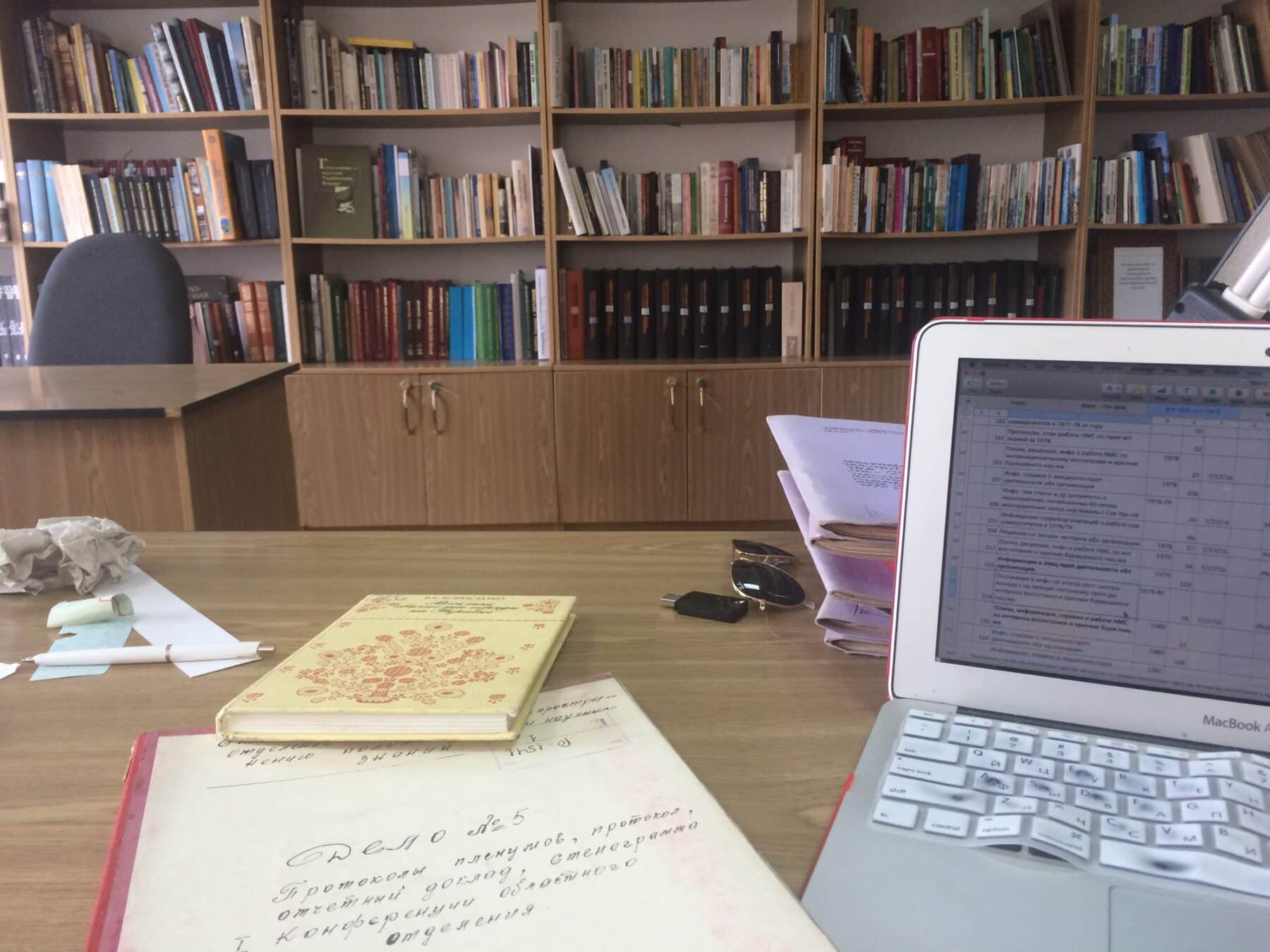

When considering how to approach my dissertation topic, I knew that questions about the ideas, institutions, and practices that unified citizens across a diverse geographic and cultural spectrum needed to be answered by extended consideration of non-Russian spaces and with knowledge of non-Russian languages. Especially early in my research, I was fortunate to spend extended periods abroad in language study and archival research, which shaped the questions and ideas that I had going into archives. This has enabled me to consider various localities on their own terms and not merely from the viewpoint of Moscow. I designed my research to take advantage of Ukraine’s and Qazaqstan’s comparative archival openness, which offered counterpoints to views from Moscow. Extended time on the ground—both in archives and talking to language teachers, host families, friends, and colleagues—reinforced that these so-called “peripheries” were never peripheral but were rather central sites where citizens navigated the possibilities, limitations, and contradictions of belonging in the Soviet Union. I sometimes think in terms of a comparison: what would it be like to study U.S. history, but do research only in Washington, D.C. and maybe New York City, and turn around to make claims about what it meant to be American? We know instinctively that this approach could only offer a narrow view, yet we often normalize this approach in Soviet history. To me, the breadth of my archival research—which expanded gradually over time, as opportunities presented themselves and the book project got stalled through contingent employment and the pandemic—provides critical perspectives on the diversity of experiences across the Soviet Union.

What are the advantages and challenges of a multilingual, multi-country archival project? What advice would you offer to scholars interested in developing projects that might take advantage of archival materials in multiple countries?

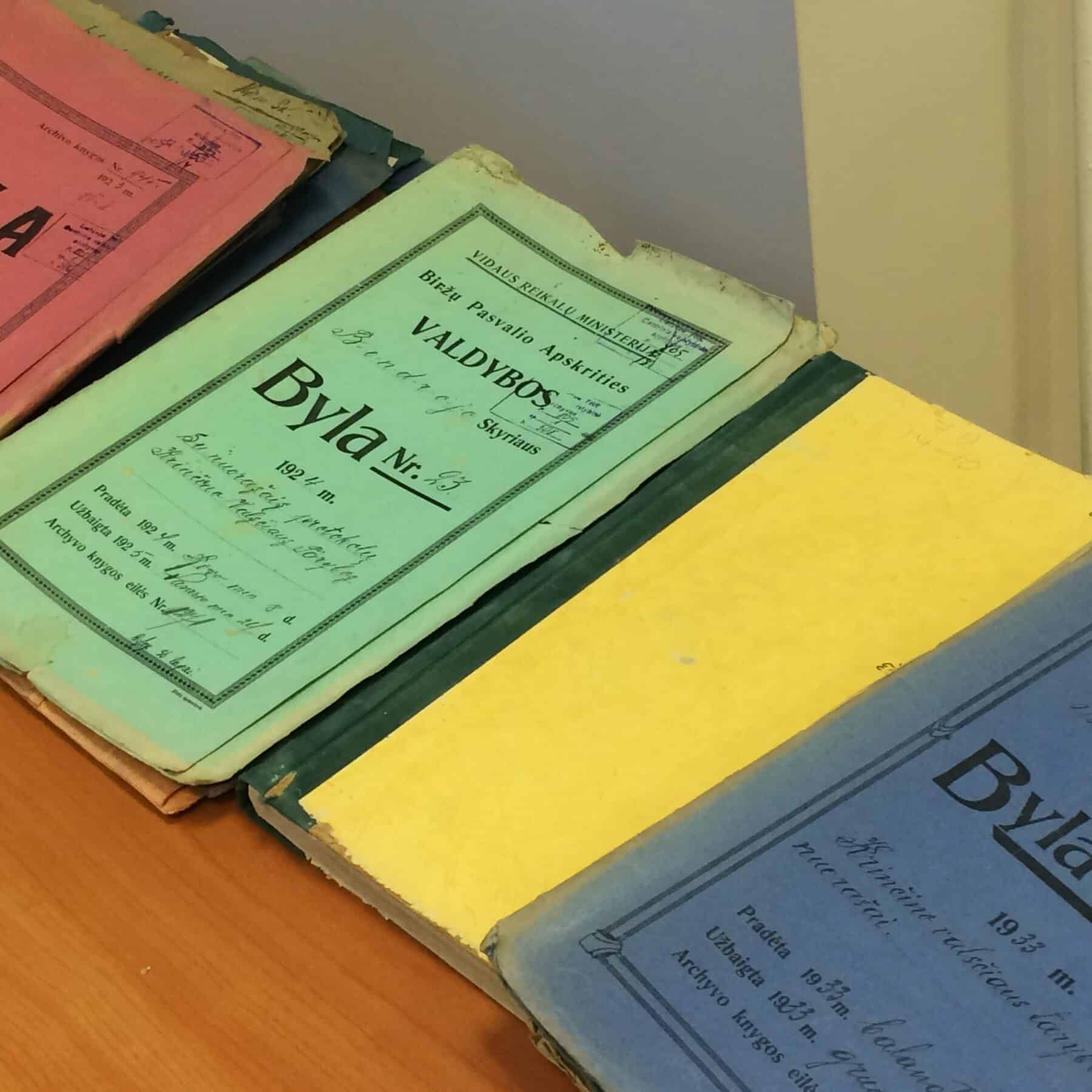

Most obviously, working in multiple countries enables researchers to take advantage of different schemes of access and availability. Ukraine and Lithuania have provided relatively open access to files of state security organizations like the KGB, and Qazaqstan is currently in the process of declassifying files related to Stalin-era repression. In other cases, certain processes are more visible at the local level—for example, the integration and Sovietization of Western Ukraine looks different from Moscow than it looks from Ivano-Frankivsk. Republic capitals give a more expansive view into the local level, whereas what got filtered up to Moscow in reports tended to be only the most exceptional cases. Research in republics can also offer insight into those Soviet institutions and practices that were quite decentralized. For my work, this includes education curricula and “new rituals” for weddings and funerals, which were typically republic initiatives. For me personally, the breadth of my research has made me more sensitive to patterns and deviations, especially as I gathered experience. This has, in turn, allowed me to work more efficiently and effectively in subsequent trips, even in new places and archives.

One benefit of researching the history of a relatively centralized and hierarchically organized country is that archives of the former Soviet Union tend to work in particular, familiar patterns, with institutions and practices that largely mirrored each other from republic to republic, and between republics and Moscow. In some respects, this makes it easy to jump into a new setting and make sense of the institutional records. At the same time, it is a mistake to think we can simply substitute research in various non-Russian republics for research that we might have done in Moscow, without considering the specific local contexts and languages in which materials are produced. Scaling up projects to include additional sites must come with increasing responsibility to grapple with local particularities. Ideally, this means finding ways to work with the materials produced in non-Russian languages, whether through language study or with the help of research assistants.

My biggest piece of advice is to immerse yourself in the languages, history, and culture of places where you plan to do research to the greatest extent possible, ideally before you go. It is a problem when we think we can parachute into new places without substantively altering our research approach. Especially problematic is a tendency to skip over documents simply because they are written in languages we cannot read. For some researchers, research in non-Russian republics has been used to add a touch of local color. Our engagement with the historiography of those republics is often limited to a book or two on an exam field, in the interests of breadth of coverage, rather than extended immersion in local questions and interpretations. Our training and research questions should evolve in conversation with the places where we do our work, and it is our responsibility to familiarize ourselves with those specific contexts and histories.

Tell us about the commonalities and differences you experienced as a researcher in libraries and archives across the former Soviet Union. What surprised you? To what extent did these experiences influence your understanding or interpretation of your subject(s)?

Archives and libraries were all part of the Soviet state, so there is a high level of familiarity when entering these institutions—even those that have opened since independence. The biggest differences are often in terms of working conditions, like how fast documents get delivered, rules and terms governing photography, the extent of various collections, and the degree of digitization. Some places make it easier to accomplish a lot in short trips, especially if you can peruse collection registers online before arrival and preorder documents. In other cases, you need longer on the ground to accomplish the same tasks. One of my biggest recent surprises was discovering that the National Library of Lithuania is a lending institution—I was somewhat taken aback when I was allowed to walk out of the library with old textbooks and a due date for returning them. The availability of Wi-Fi at the National Archives of Estonia, in Tartu, was likewise a delightful discovery—as was the rapid delivery of documents, often within half an hour. Other places remain significantly more bureaucratic, requiring more time and sometimes connections to do the work you would like to do. It took me months to be allowed into the Central State Archive of the Republic of Tajikistan—and that was a best-case scenario.

On a more intellectual level, my biggest impression from more than a decade of archival experience is that the Soviet Union was far more complex, varied across regions, and diverse than we often appreciate. In almost all cases, policies conceived in Moscow had to be realized, adapted, and interpreted on the ground in diverse communities, members of which participated in central policies and pushed local initiatives on their own terms and in pursuit of their own goals. While we of course know this in theory, realities are even more messy on the ground than we sometimes expect. The stories we tell from Moscow almost never grapple with that full complexity, other than to gesture toward it. I also have found that attempts to understand, document, and work with non-Russian peoples were highly developed and sophisticated (if not always successful), something I came to appreciate primarily through materials in non-Russian languages.

What new challenges of archival research, particularly but not exclusively pertaining to the Soviet Union, have emerged since the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine? What other challenges do you see impacting this field? How do these challenges resemble or differ from, for example, those which scholars faced prior to 1991?

Our current challenges operate on several levels. Most concerning are the ones faced by those living and dying in the region we study, especially Ukrainians who have taken up arms, live under occupation, or are threatened by missile strikes. No discussion of our challenges as researchers should begin without an acknowledgement of the severe crisis facing Ukrainians, including scholars whose academic institutions and homes are literally under fire. I also worry about the physical destruction of libraries, archives, cultural sites, and academic institutions. There are also the separate and different challenges facing Russian citizens who oppose the war, especially those speaking out and facing consequences, and those experienced by citizens of other former Soviet countries living under authoritarian regimes of various stripes.

As researchers in the U.S., our challenges are less grave, but the work patterns to which we have become accustomed are nevertheless changing substantially. I was lucky to come of age as a historian at a time of archival excess. Of course, there have always been limitations to the topics available for research. Archives themselves are products of the historical conditions that determined what was to be catalogued as part of the historical record (and what was not). Still, it is sobering to think of the changed archival landscape, as most of us choose for moral but also institutional, financial, and safety reasons to avoid Russia.

Immerse yourself in the languages, history, and culture of places where you plan to do research to the greatest extent possible, ideally before you go. It is a problem when we think we can parachute into new places without substantively altering our research approach.

In most respects, we are in a far better place than before 1991, both because of the wide range of archival access across many parts of the former Soviet Union and the many collections of published documents that have appeared in the interim. Even without being able to research in Russia, I am confident people will continue to produce nuanced, innovative histories, perhaps now with more attention to the impacts of policies in non-Russian republics. In general, we have tended to prioritize archives over the enormous storehouses of published sources and digitized materials, so a little course correction to take advantage of such materials is a welcome development.

Thinking long term, perhaps the biggest challenge created by the combined effects of both the pandemic and Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine is that our students have limited first-hand experience with Russia, and in some cases, with international travel at all. This is already true for undergraduates, who saw programs resume in Russia post-pandemic only to have them cancelled in the wake of the full-scale invasion. Even many of our graduate students have now never been to Russia. Sending students to places like Almaty, Bishkek, or Daugavpils certainly fills in some of the gaps in terms of language study, but we need to encourage and guide students to consider what it means to study Russian in sites of Russian/Soviet colonization, where Russian remains prominent because it was the language of empire. This requires sensitivity and attention to the specific histories of places where students now study. In an ideal world, such programs would include introductory instruction in local languages.

One other major challenge we face as a field is the dramatic decline in investment in language study, which becomes an especially acute problem as the linguistic demands of doing research increase. As students and researchers head to non-Russian republics for research, it will be ever more necessary to have not only Russian proficiency but also additional languages of the former Soviet Union. Increasingly, however, students struggle to get where they need to be even for Russian. While Russian-language instruction was never universal, many universities have scaled back or eliminated language departments and removed foreign language requirements. The decreased emphasis on study abroad, too, has cascading effects on language proficiency. Meanwhile, AI-driven translation tools—while invaluable—contribute to a general undervaluing of linguistic skills. I would love to see more prospective PhD students embrace MA programs in area studies as critical stepping stones for future academic careers. These programs develop necessary skills by providing advanced Russian language instruction, creating pathways for studying non-Russian languages, honing research and writing skills, and deepening area studies knowledge in a holistic sense. Many prospective students, however, prefer to apply straight to PhD programs, figuring there will be time to cultivate the language skills necessary. There often isn’t, especially if students are still working on Russian. There are some positive signs, though. I am especially heartened by the growth of online consortium-style programs for less commonly taught languages. Institutions like the University of Wisconsin, Indiana University, and Arizona State University have long been on the forefront of offering summer language programs for more rarely taught languages. Still, we need both significantly more investment in teaching languages and more acknowledgment as a field of the importance and value of language study.

How have you seen scholars adapt and react to this changed landscape? What tips or resources would you offer to scholars currently planning research travel to archives in the former Soviet Union?

Historians are resilient and are responding in many ways. For one, there is more and more work that takes advantage of the myriad published materials available in libraries across the country. I am especially proud that my own university, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, sponsors year-round programs that enable researchers to access our incredible library collections as part of our mission as a public institution. Researchers benefit from our tireless Slavic Reference Service, as well as the academic year Open Research Laboratory and Summer Research Laboratory, which are run by the Russian, East European, and Eurasian Center. I’ve seen lots of exciting new work that relies mostly or even entirely on published materials. Those with active library cards from the Russian State Library (“Leninka”) can also take advantage of enormous troves of digitized materials. In many cases, our obsession with archives has meant we have underutilized the materials most readily available. There is so much innovative scholarship that can be done without setting foot in an archive.

People are also adapting by researching in new places, traveling to countries that were not really on their radars as places to do research until possibilities of researching in Russia became foreclosed. I suspect the net result for our field will generally be positive, as current conditions force more scholars to reckon with the diverse landscapes, societies, and citizens that once comprised the Soviet Union. There are also microfilmed versions of archival documents available in the U.S., including at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University, the Library of Congress, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

For those planning to do research, I especially recommend reading up on the histories of the places you are going, contacting scholars who have worked in the archives you plan to visit and are willing to share their experiences, and perusing all reference materials available, including both online and published guides. This is enormously important in planning visits and making the most of limited time on the ground.

Long before the dramatic opening of archives, historians were often on the forefront of creatively addressing the difficulties and limitations of sources. Being a good historian has always required a degree of flexibility, nimbleness, and creativity in unpacking the nuances and complexities of the past. It is important to remember that archives are not so much an end in themselves, but one tool among many for telling nuanced, complex histories. Even with some curtailing of archival access, we have still never had so many tools at our disposal—it is our job to take advantage of them!

Anna Whittington is a historian of citizenship and inequality in Soviet Eurasia. Her in-progress book manuscript, Repertoires of Citizenship: Inclusion, Inequality, and the Making of the Soviet People, explores the discourses and practices of Soviet citizenship from the October Revolution to the Soviet collapse. Drawing on sources collected in more than 30 archives and libraries in nine countries, the book demonstrates that Soviet leaders promoted a civic identity built on active participation in public life. People embraced this vision of equal citizenship cross a wide geographic and cultural spectrum, even as ethno-linguistic, racial, gender, and spatial differences created disparities in their claims to this identity. As the book shows, the Soviet rhetoric of equality, inclusion, and multiethnic representation coexisted with systemic inequalities that shaped lived experiences. Inclusion and inequality were both fundamental to the articulation and experience of Soviet citizenship. Professor Whittington has also begun research on two additional projects. The first, tentatively titled A Mirror for Society: Censuses in the Russian Empire and Soviet Union, explores the history of enumeration, while the second, Cacophony: The Unmaking of the Soviet Union, considers the Soviet collapse from the grassroots level.