A version of this article previously appeared as “Historical Empathy, Creativity, and the Unessay,” Agora 58, no. 3 (2023): 59-64.

The unessay as an assessment tool has grown in popularity, particularly in tertiary history classes. Instructors empower students to choose their genre to produce a research-informed creative engagement with the past. Short stories, board games, video games, and children’s books are all common unessay format choices. Other possibilities include cooking blog posts, sewing projects, comedy skits, and “radio play” podcasts. The freedom to choose the form for presenting research and argumentation gives students the chance to draw on skills and passions that would not typically make their way into the history classroom.

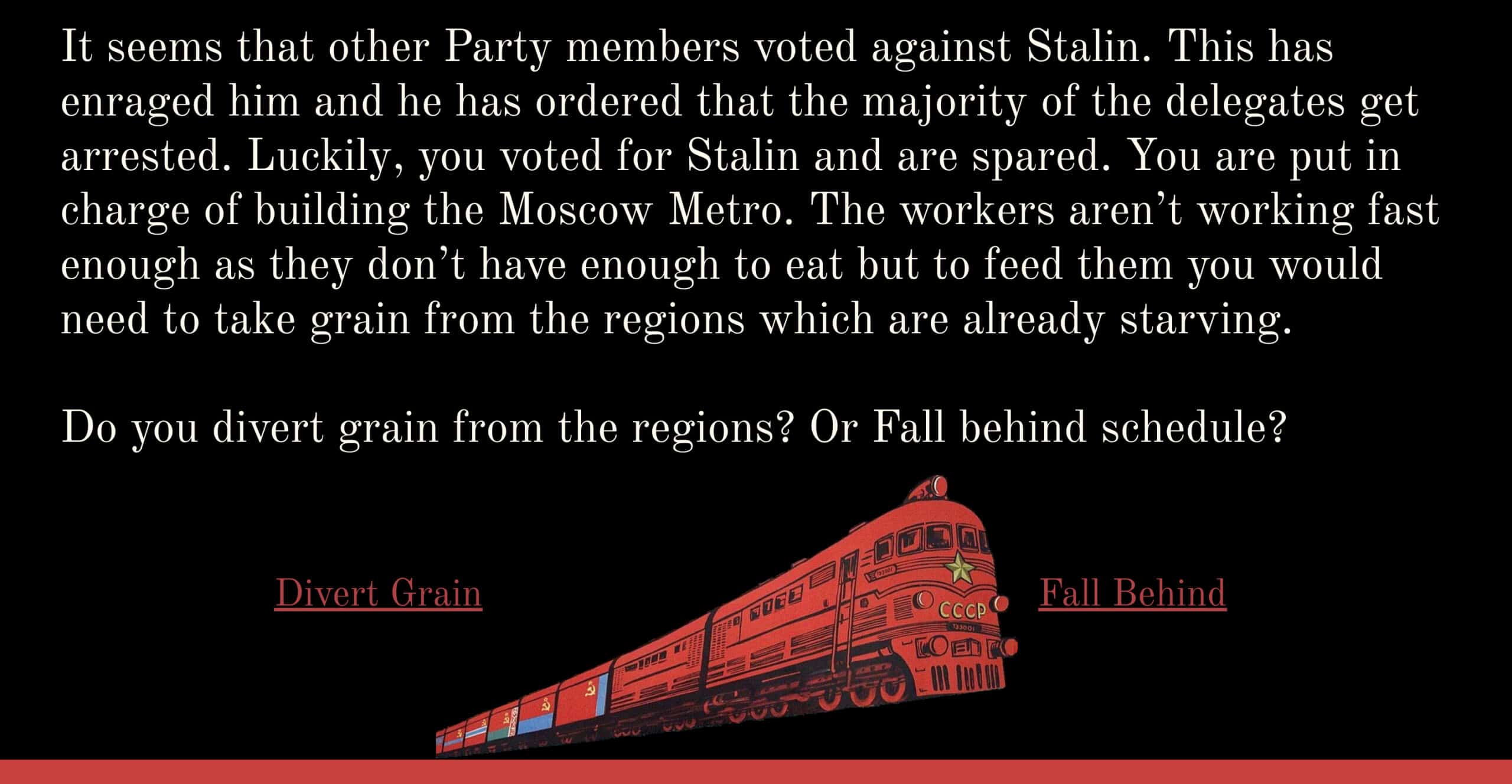

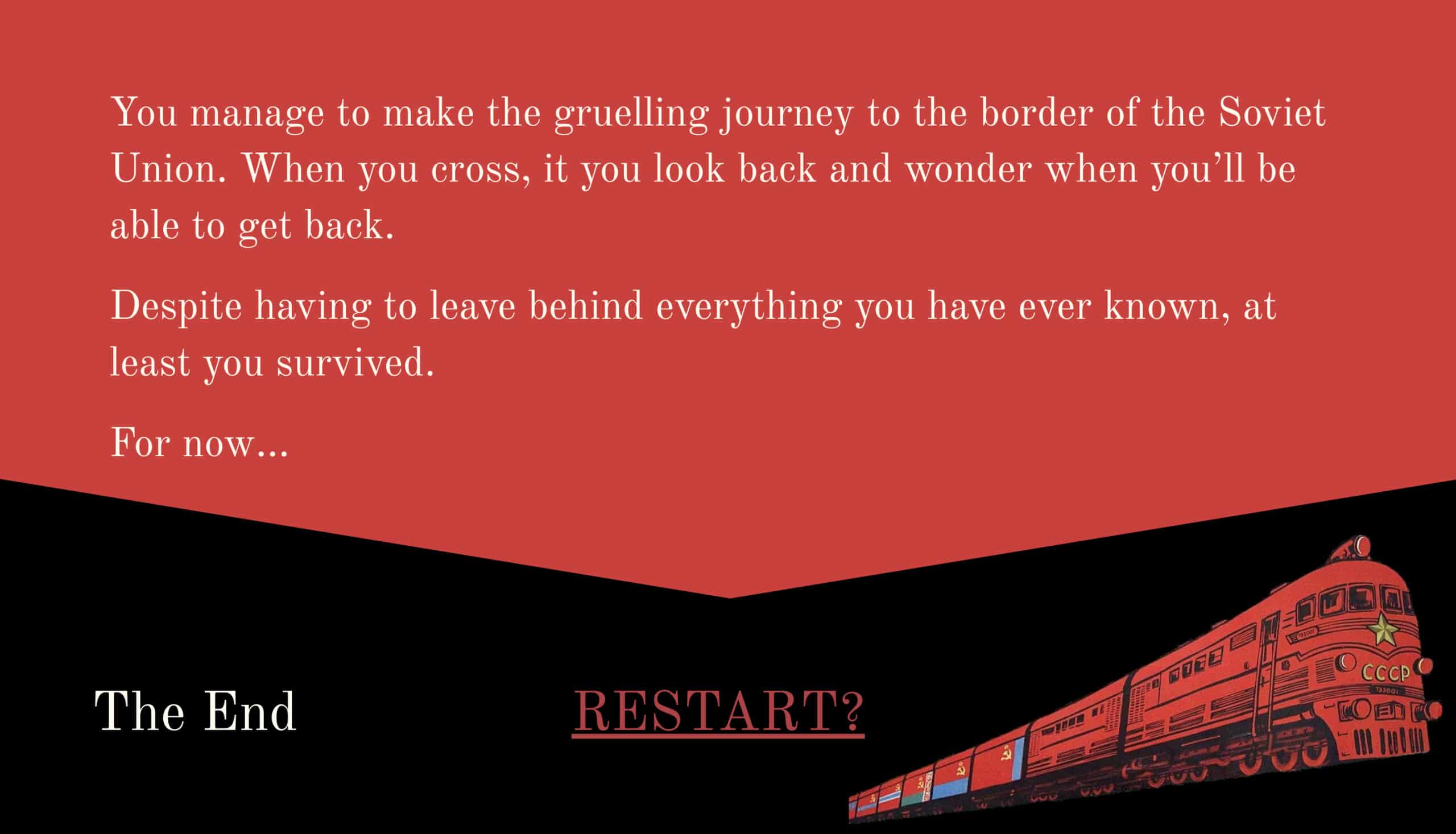

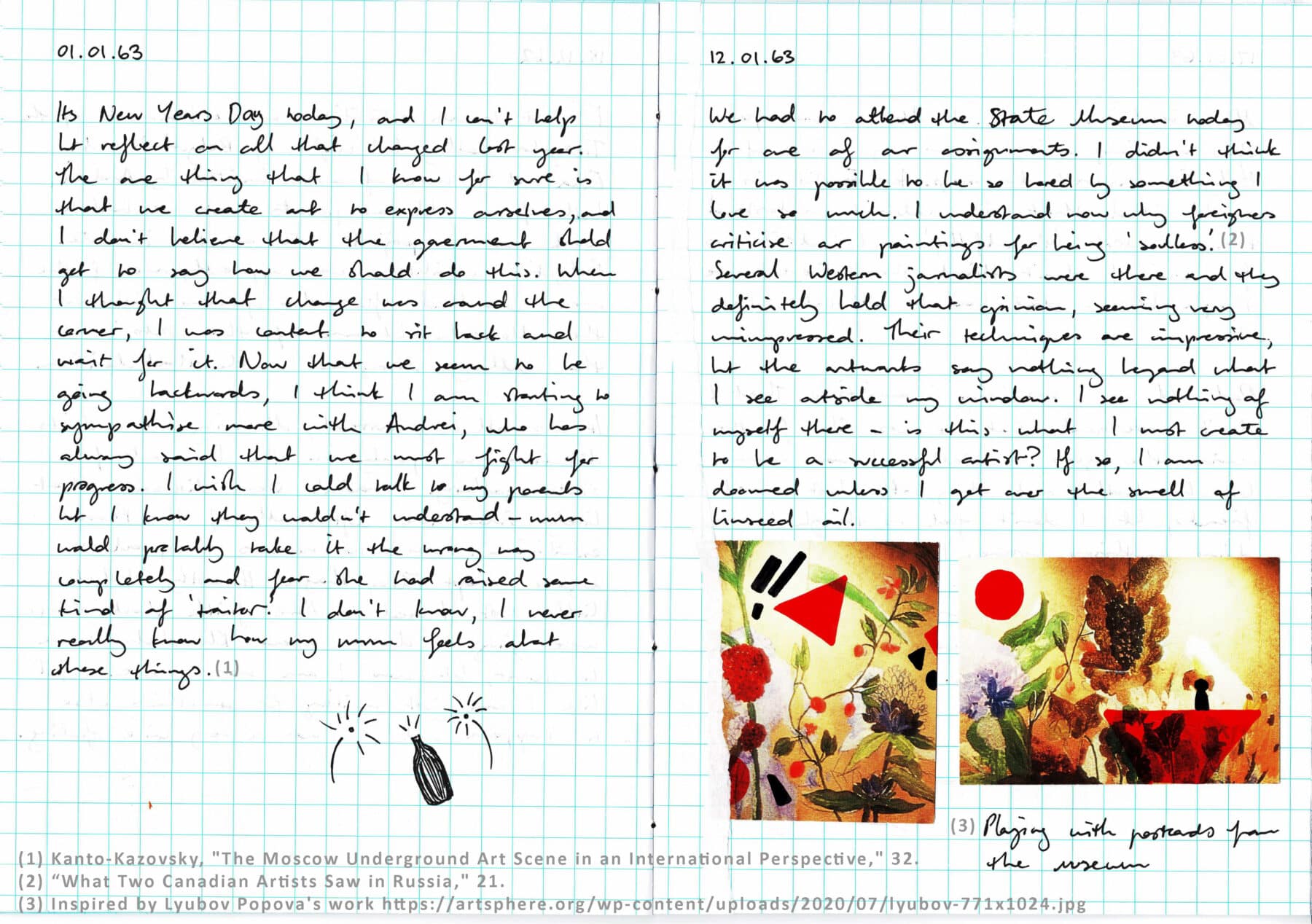

In this article, we offer an experience report on the use of the unessay in an advanced undergraduate history class at a large public university in Melbourne, Australia, but the observations offered here have implications for other national and educational contexts. Michaels served as primary instructor, supported by a teaching assistant. She had intermittently used the unessay but, in 2021, she overhauled the course’s organization, assigned texts, and assessments to support student choice of the unessay option. Coauthors Claire Dowling, Katherine Robertson, and Kelly Lin Huai Wong were undergraduate students who chose the unessay. Dowling used PowerPoint to construct a choose-your-own-adventure (CYOA) game called “Surviving Stalinism.” Her objective was to demonstrate the mix of agency and luck that drove personal fate. Robertson composed a diary from a purported art student in the Khrushchev era (1953-64). She wrote the diary entries in a handmade book styled after a 1960s’ Soviet composition notebook, enhanced with marginalia inspired by Soviet artists. Wong composed an instrumental piece of music in the spirit of Dmitrii Shostakovich (1906-75). She used all aspects of the music—instrumentation, pace, tone—to tell the story of his effort to navigate a safe path of creative expression during the repressive years of the Stalin regime (1928-53).

The unessay offers a path to two significant learning outcomes: creativity and empathy.

To analyze our experience of the unessay as an assessment tool, we organize this article into six sections. The first section briefly lays out the pedagogical case for the unessay. The second section details the assessment’s implementation. The next three sections of the article offer reports from Dowling, Robertson, and Wong, respectively, on the student experience of the unessay. Unlike other parts of this article, these three sections are written in the first person. The remaining sections are written in a collaborative voice (we) or, where appropriate, with reference to the subject by an individual author’s surname. We conclude with summary comments regarding our insights about the experience and recommendations for others seeking to implement the unessay as an assessment tool.

The pedagogical case for the unessay

Beyond mere mastery of historical content, the unessay offers a path to two significant learning outcomes: creativity and empathy. As Sheila McManus puts it, the unessay promotes “imaginative questions, intuitive connections, empathy, and the passion that drives many historians.” As a deeply active task, the unessay bridges cognitive and affective processes to promote “perspective taking” or “positionality.” Critical engagement with the past demands understanding it on its own terms, without projecting present-day knowledge and norms. Critical awareness of one’s own positionality, as well as that of historical subjects, is essential. As three Finnish educators wrote in their description of historical simulation for high schoolers, such creative activities “allow the student to step into a historical figure’s shoes and to fill in the missing blanks in a historical narrative with knowledge-based imagination.” Students who undertook the unessay report similar empathic experiences prompted by creative engagement with the past. As Robertson put it in our conversations while writing this article, the unessay prompted her to read “beyond just what’s written” in primary sources.

However, it is impossible to fill the gaps between sources imaginatively but plausibly without sufficient understanding of the motives, constraints, and worldview of past actors. Students who undertook the unessay drew on the context provided in the course content, supplemented substantially by their further primary and secondary research. In tutorials and consultations, Michaels underscored that the research component of the unessay was the lynchpin because, as with role play and simulations, it ideally framed and informed the entire imaginative process.

The unessay assignment

Titled Life in the Soviet Union, the course emphasized history from below, seeking to draw students’ eyes away from high politics and ideology to the lived experience of ordinary citizens. Texts included English-language translations of diary entries, memoir excerpts, letters, newspaper articles, anecdotes, and films, which were supported by a textbook and selected secondary readings.

In the first week of the twelve-week semester, students received detailed written information on all assessment tasks, including a “research project.” The document outlining that task specified that students had two options for the “medium of expression”: a conventional essay or an unessay, with the latter allowing:

for a creative/imaginative engagement with the past, while still staying grounded in an evidentiary source base. … The creative submission is limited only by your imagination. It has one goal: to demonstrate engagement with a topic related to the social or cultural history of the USSR. It can take any form, including, but not limited to, the following: historical fiction short story; an imagined “private,” “primary source” (letter[s]; diary entry/ies); political poster; poem; song; graphic novel; comic strip; zine; children’s book; board game; painting; podcast interview with a fictional character or historical figure; craft project (a meal, felt boots [valenki], wooden toy, needlework).

Alongside the creative submission, students had to turn in a bibliography and an exegesis that explained the research question and how the creative work responded to it. Students were encouraged to search the internet for explanations and examples of unessays; sample work by students in previous years were also shared on the online learning platform.

Whether students chose the unessay or the essay, across the semester they received guidance and produced scaffolded, formative assignments aimed at supporting the research project. In week 5, brief video “tours” and an online lesson helped students to navigate the relevant newspaper databases. In week 6, students submitted a 25-word, unmarked statement of their proposed topic. In week 8, students were assessed on a research question and annotated bibliography, worth 25 percent of their final grade. By this point, students had to have decided whether they would produce an essay or an unessay. A one-on-one consultation with the instructor was required before a student could proceed with the unessay. The intention was to prompt thinking through the relationship between form and content. In weeks 10 and 12, time was set aside in tutorials for group discussion of research projects, with a focus on peer-to-peer learning for workshopping contentions and navigating research obstacles.

The next three sections offer insight into the experience of “doing” the unessay with reports from this article’s student authors. They lay out observations on their cognitive and affective experiences. Taken together, they attest to the unessay’s significant educational outcomes in line with the task’s objective, beyond mastery of specific historical content, to cultivate empathy and creativity.

Surviving Stalinism (Claire Dowling)

“A challenge of the history unessay is that, to get at the first-person perspective, one needs to lean on primary sources, especially documents like diaries, which offer a window into personal experiences. I had to derive logical, realistic choices in my CYOA from diaries and other secondary sources to gain adequate context. For a Soviet history class, accessing such sources in English demanded time and perseverance. While engaging, the unessay was by no means the easier choice, as my research involved combing carefully through more material than I usually would have for a traditional essay.

With almost endless possibilities, the loose, open structure of the unessay is both a help and a hindrance. Like a traditional essay, there is the problem of ensuring one’s contention addresses the research question and is easy to follow. However, in an unessay, this is even more important, as it guides not just the content, but also the form. The most important advice I received when I was struggling with the unessay was to ask myself “what is the point of this work?” This question is relevant to all forms of research but was something I had not considered for traditional essays as the point of the work was always just to write an essay that would earn a good grade. Thus, the unessay forced me to think more deeply and explicitly about how and why we do research.”

Art in the Khrushchev Era (Katherine Robertson)

“I was surprised to discover that the research itself for an unessay differed significantly from that of a conventional essay. I believe students, and perhaps some instructors, tend to think that the unessay requires less research than a traditional essay. This was far from my experience. The unessay demanded the same, if not more, research to situate and deeply contextualize the primary material properly. I had to think critically and creatively about the broader social contexts and synthesize large amounts of information. In other words, I was compelled to mobilize research and analytical skills at a high level. In creating the fictional characters and the relationships required for the unessay, I had to move beyond reporting what my research uncovered; instead, I had to construct a vision of the past that I then to some degree projected myself into and inhabited.

This process of researching and producing the unessay provided a valuable learning experience on the place of empathy in historical research. By researching in depth the relationships between people and art and using this knowledge to construct a fictional but historically-informed world, I related to them on a personal level. I found myself appreciating the uncertainty of living in the Khrushchev era as a young artist, or as someone interacting with art. Previously, when writing a conventional essay on similarly complex subjects, I intellectually understood conflicting motivations. Through the unessay, I grasped them on an added emotional level. One of the pitfalls for history students is to judge past actors by modern values. I found that the unessay helped to limit this inclination toward presentism, as I was able to put myself in my protagonists’ shoes. I felt compelled to represent the past as authentically as possible, within the constraints of using only English language sources. It offered an invaluable lesson on the role of historians as the curators of the past and the need to fulfil this role conscientiously.”

Shostakovich and Stalinist Terror (Kelly Lin Huai Wong)

“Knowing that I would ultimately try to compose an original piece of music gave me a new perspective on primary and secondary sources. In my analysis of the original scores, I thought about the musical decisions and techniques applied and how this might be a source of inspiration. In imagining myself in the position of a composer during the Great Terror, questions of agency and freedom arose. Shostakovich was no longer some distant historical figure, but an intelligent, frightened man responding to denunciations in creative ways, embedding messages in his music. This process provided insight into the intentional nature of musical composition, fostering a sense of historical empathy for Shostakovich and his careful compositional process under the watchful eye of the Soviet state.

My unessay research supported the composition process amid an anxious swirl of uncertainties. Boundaries were ill-defined in assessment instructions due to the personal nature of each project. This flexibility was both the greatest benefit and drawback of the unessay, providing space for creativity, but also bringing a sense of uncertainty. Specifically, I was unused to having to define the scope of my own project and lacked confidence in my ability to execute it.

Beyond composing the piece, articulating my ideas and findings to a non-musically literate audience posed a significant challenge. In many ways, my chosen genre helped; instead of using words to convey a musical concept, I could demonstrate it. The piece showed, rather than told, how Shostakovich’s musicality and affective impact changed over time. But communicating my creative vision and its connection to my research findings was difficult to achieve through the exegesis alone. I had to consider accessibility to the listener. Michaels cautioned me that she could not read music and knew little about it. We agreed that an annotated version of the score, explicitly breaking down the decisions made, accompanied by a video to help her to understand the piece would be beneficial. The annotations helped me to think even more deliberately and explicitly about my intentions.”

Conclusion

Reflections from this article’s three student authors point to the ability of the unessay to inspire active learning. Across the varied forms and contents of each project, our comments demonstrate how we each achieved a deeper understanding of Soviet history, grappled with questions of historical contingency, experienced a sense of historical empathy, and engaged creatively with the past. Through our conversations when writing this article, it became clear that we all viewed the unessay as demanding more extensive research, which threatened to grow the project to unmanageable proportions. Despite this challenge, our observations about how and what we learned point to the development of critical and creative thinking.

Michaels, for her part, came to appreciate more fully the unease and confusion that comes from grappling with such an unbounded assessment task. It is imperative for expectations to be clear and parameters to be explicitly circumscribed. Tight, firm deadlines are required for scaffolded assignments. Students require repeated reassurance about expectations for scope and quality.

Our experience suggests that one of the most important aspects of the assessment design is the submission of an annotated version of the unessay, which helped to alleviate student concerns about how their work would be assessed. As Wong observes, the annotations allow the student an opportunity to tether the research directly to specific creative decisions. For the instructor, they work like footnotes to explain where elements originate and to render visible the student’s intentions. While the unannotated version allows for a direct experience of student creativity, for the purpose of assessment, the annotated version offers a clearer diagramming of the underlying research.

In closing, we note that all the student authors were pursuing double majors that paired with disciplines outside the humanities: Engineering (Dowling), Science (Robertson), and Education (Wong). Perhaps it is no coincidence that the unessay task appealed to students with varied interests. In classrooms where students come with different levels of engagement and skills, the unessay offers a mode of assessment that plays to a wide range of strengths to cultivate a creative, empathic engagement with the past.

Paula Michaels is an associate professor of History at Monash University (Australia). Distinguished by its transnational and comparative approach, her research examines the social history of medicine in the USSR. She is currently at work on a study of Soviet medical internationalism and the global Cold War.