Anatoly Pinsky

Associate Professor, Department of History, European University at St. Petersburg

When did you first develop an interest in Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies?

I was raised in the United States, in a Soviet émigré family, but began to take an interest in Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies only in college, at Northwestern University. There, when I was a first-year student, I took a course on nineteenth-century Russian literature with Gary Saul Morson – we spent a semester reading Anna Karenina and The Brothers Karamazov – and thereafter I became fascinated with the field. I was a History major and changed my area of concentration from American to European (at Northwestern, Russia was part of “Europe”), David Joravsky became my advisor, and I also took a course with John Bushnell (I wish I had taken more). I am enormously indebted to professors Morson, Joravsky, and Bushnell, all of whom were simply excellent teachers.

How have your interests changed since then?

To what became enduring interests in nineteenth-century Russian literature, European intellectual history, and Soviet history, I have added interests in Soviet literature, literary theory, and anthropology. When I was in graduate school, at Columbia, one of my professors, Richard Wortman, really emphasized the value of casting a wide disciplinary net.

What is your current research/work project?

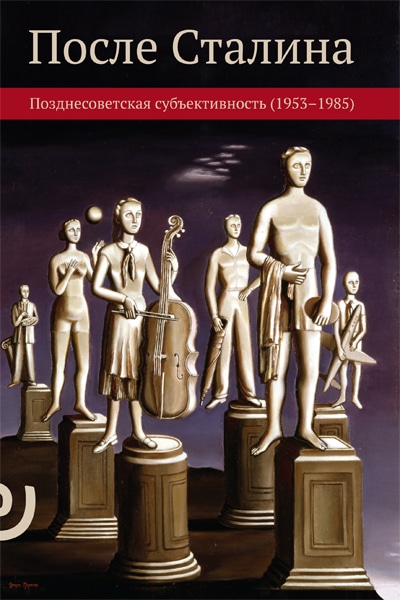

I am also working on a book, tentatively titled “Soviet Individuality: A Study of Self and Form,” which examines the rise of what I call an ideal of individuality and related literary forms in the mid-twentieth century Soviet Union. My subjects are well-known Soviet writers, including Aleksandr Tvardovskii, Fedor Abramov, their friends and family members, as well as a variety of other writers.

What do you value about your ASEEES membership?

Everything – the subscription to Slavic Review; the access to NewsNet; and, above all, the annual convention, which gives me the chance to return to the States and talk to old friends and colleagues about their research and goings-on. Also, the convention panels offer such a variety of topics that I am able to create a mini-conference each year for myself based on whatever I happen to be focusing on that fall.

Besides your professional work, what other interests and/or hobbies do you enjoy?

I wish I had more time to read literature unrelated (at least directly) to my own work. My wife and I tried to combine a mutual desire to read more widely with being new parents, and so in the evenings began to read David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest to our newborn. We got to page 223 before we chose to trade DFW for sleep. At present our boy enjoys lighter reading in the evenings, for example, Поросенок Петр.