Over the past two years, Ukrainian studies has not only gained popularity as a subject of research and teaching, but also emerged as a methodological focal point for practical and theoretical integration. However, for obvious reasons, there has tended to be a focus on contemporary topics—namely, the ongoing war. Despite expanded coverage in the West, in particular in the media, Ukraine is still primarily known and discussed through stereotypical narratives about the Euromaidan and Russia’s invasion and annexations. Admittedly, forced contemporaneity is hardly unique to Ukrainian studies, but rather is general to the humanities, which in recent decades finds itself in a precarious spot: on the one hand, having to “win” relevance in a public space and among the student population, hence influenced by popular trends; on the other hand, striving to retain its “classical” foundations in researching and teaching universal knowledge about humankind’s experience in a historically comparative perspective.

If we peruse the (recently quite expanded) range of courses in Ukrainian studies, whether offered by longtime Ukrainianists or those now beginning in the field, or courses that integrate Ukraine as a key part of their curriculum, we find a glaring focus on the post-Soviet, or even post-February 2022, period. Less attention is paid to Ukraine’s longstanding multiculturalism and identity politics, or to how these historical constructs fit within current international debates on race, gender, and queer subjects. Similarly, while topics like slavery and forced labor are quite familiar to North American students, how these issues relate to the Ukrainian context is virtually unknown to academic and lay audiences.

Ukrainian studies was not born on February 24, 2022.

As we follow ongoing debates among colleagues who are making valuable efforts to establish and expand Ukrainian studies as more than just a derivative of a popular trend (in academia and beyond), it is heartening to see attempts to indeed sustain students’ interest in the field creatively and contextually, including topics that are not directly tied to the contemporary moment. I too would like to take up this challenge, and in this I feel a solidarity with all Ukrainianists, who now face their field’s crucial, and exciting, transition. While the current context will naturally be present and is indeed vital, we can explore and emphasize areas that extend beyond immediate events. To put it bluntly: Ukrainian studies was not born on February 24, 2022. All the rich history, culture, and literature of this field existed before, and will exist when this war is over.

One of the topics I’d like to discuss here concerns the not-so-distant past, and a matter familiar to North American audiences—slavery. At the same time, I am interested in exploring the implications of researching and teaching things that may be perceived as less topical; how might we change such perceptions, taking something “irrelevant” and showing its direct pertinence to the present moment. This involves teaching topics that fit current international and cross-cultural trends and considering their place in contemporary debates that are top of mind to our students. The goal is to attract them through multidisciplinarity, stimulate their thinking, and situate the material within the up-to-the-minute contexts and media they are already familiar with.

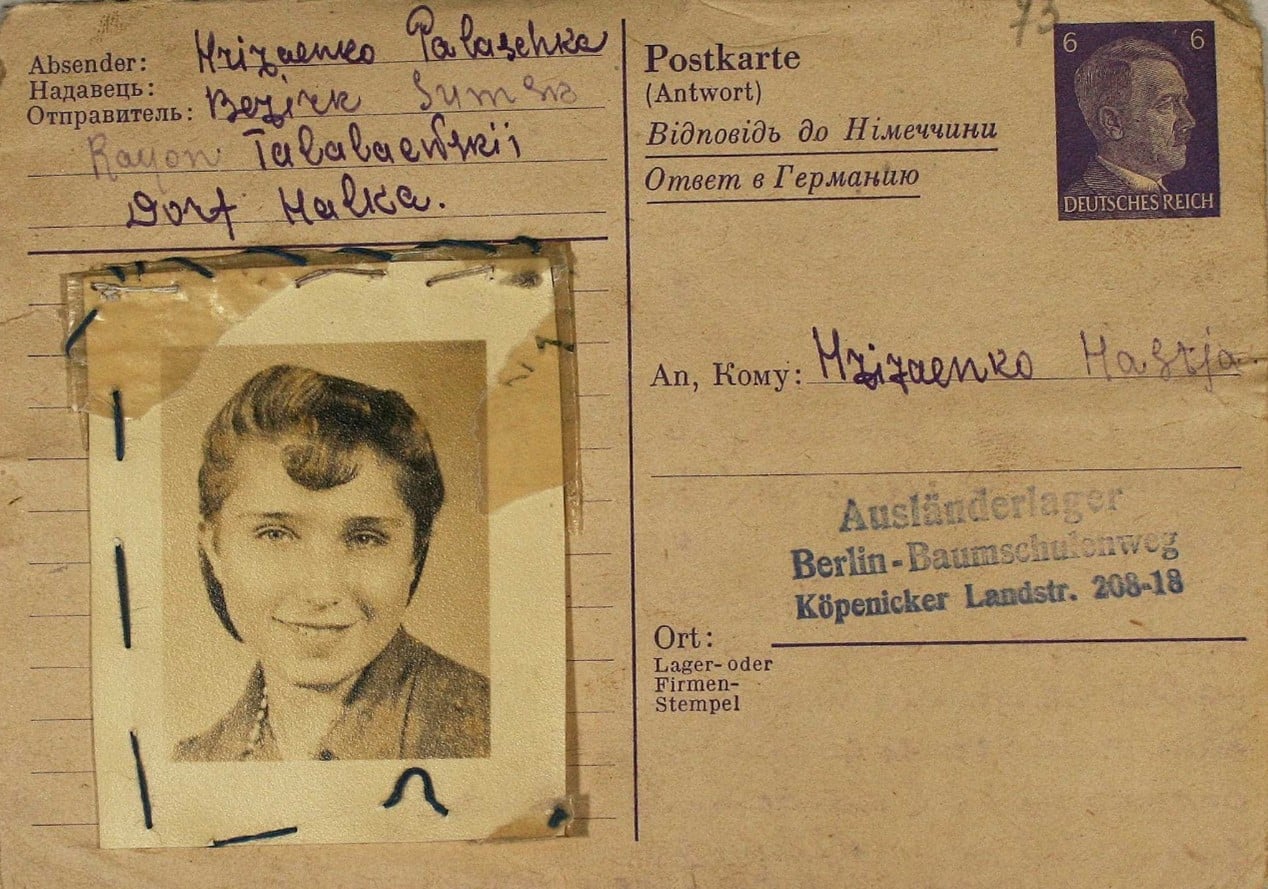

In my research and teaching, I have always been drawn to the use of art—textual, visual, tangible—in non-artistic settings like imprisonment and slavery, where a captive’s creative output provides uniquely valuable testimonies. During the Second World War, nearly three million Soviet citizens, predominantly Ukrainians, were forcibly transported to Nazi Germany as Ostarbeiters (“Eastern workers”). These people were permitted to send letters and photographs to loved ones back in occupied Soviet Ukraine, which constituted a key emotional outlet. However, their correspondence was censored and their letters and photos were also used for propaganda purposes, to falsely project an image of the Ostarbeiters’ “wellbeing” in Germany and to encourage the recruitment of additional forced laborers.

I analyze Ostarbeiter correspondence as literature, historical sources, propaganda, and channels for both news and secret messages. Through a transdisciplinary approach, I explore these letters’ literariness (rhythm, rhymes, Aesopian language), their accompanying photographs, and the picture postcards provided by the Nazis to project “benevolence.” I juxtapose totalitarian control of communication with the letter-writers’ creative resistance thereof, arguing that their correspondence blurred the lines between private message, public newsletter, and historical testimonial. I also examine how Ostarbeiters’ photographs served as tools of Nazi propaganda, while covert messaging within these materials challenged stereotypes and oppression. These topics extend beyond slavery and totalitarian propaganda to include artistic strategies for conveying any taboo or subversive ideas. Unfortunately, these themes remain relevant today. Ukrainian prisoners of war in Russia, for example, are subject to restrictions on their correspondence similar to those imposed on the Ostarbeiters, making this project pertinent to contemporary debates on the control of knowledge during wartime.

The experience of the Ostarbeiters is a significant part of Ukraine’s history; many families have a relative who was forcibly taken to Germany for labor. This period remains one of the nation’s most profound personal and historical traumas. For Ukrainians, captivity is an all-too-familiar theme, with creative reflections on forced labor in Nazi Germany taking their place in a long tradition of artistic portrayals of captivity, from the Tatar-Mongol era in folklore, through Siberian exile, and the writings of Ukrainian Gulag prisoners, linked to a broader history of captivity and oppression, including the abduction of Ukrainian children by Russia today. Adding to the complexity is that Ostarbeiters’ correspondence often blends genres, such as “letter-poems” or “photo-hints.” I link literariness as “secret writing” to photographic elements, totalitarian propaganda, resilience through creativity, and stigmatization. My goal is to re-actualize these topics, inscribing them both in current events in Ukraine and within international discussion of negative stereotyping and adaptive resistance. Beyond connecting the topics of occupation, propaganda, and resilience in the Second World War era and now, I also emphasize the importance of openly addressing the current stigmatization of Ukrainian citizens in Russian-occupied territory, comparing it to the disaffiliation experienced by Soviet Ukrainians during occupation and after.

However, these topics are also international. There is extensive scholarship on slavery and its artistic reflections in both North and South America, and the topic is prominent in memory studies, the study of racial politics, and public-historical awareness at large—all of which has relevance to the topic of forced labor in the Nazi Reich. In my writing, I often draw for support on these well-explored non-Slavic contexts, as they are better developed than the treatment of slavery in Slavic studies. It is my hope that one day, a student of mine will write a paper on these connections.

The role of photography, both in propaganda and in depicting slavery, is likewise relevant beyond the Slavic context. Visual representations of race and/or slavery have served propagandistic purposes in many international settings, often tied to colonialist narratives present during the Second World War. While these connections might seem obvious (i.e., Confederate depictions of the “happy slave”; Nazi conceptions of “fraternal” Eastern workers), incorporating them into syllabi on Ukraine or Eastern Europe is not always straightforward, and to some may even seem a “stretch.”

The goal is to expose the multi-layeredness of my materials and to create personal attachment to them.

Using photography, I want my readers and students to encounter, standing behind these grand narratives, particular individuals: to read their letters and take a look at the real faces of the people in photographs, each of whom has a name and a story. My project zooms in on the personal relationships, loves, and experiences of women, teenagers, and children who, in different forms, were dehumanized but often also resisted. So, the goal is to expose this multi-layeredness of my materials—their contradictory messages—and to create personal attachment to them, through their textual and visual individuality. I’d imagine in the future asking students, among creative writing assignments, to respond to one of these letters, to “get in touch” with the person behind these lines and pictures.

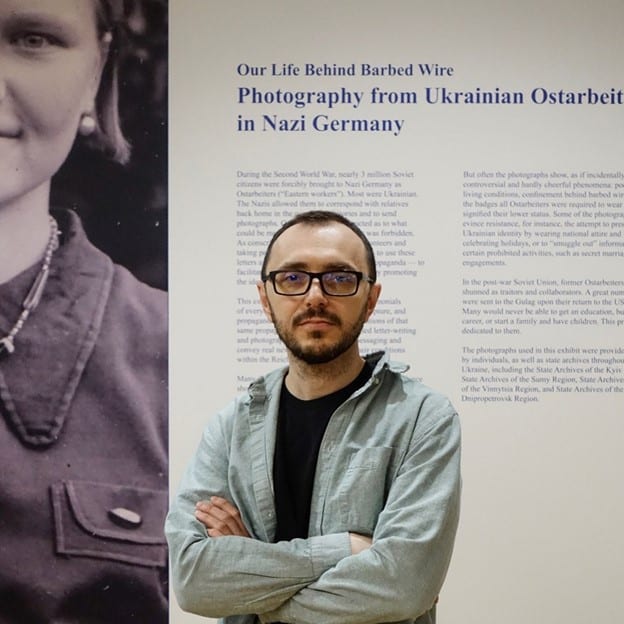

Since April, as part of my postdoctoral project at Harvard’s Davis Center, and in collaboration with the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, I have been curating an exhibit of Ostarbeiters’ photographs and letters. This exhibit explores the inventive ways these slave-laborers managed to bypass totalitarian censorship and secretly send messages to their families. It presents sixty large-format photographs, accompanied by excerpts from Ostarbeiters’ letters, as well as regulations on correspondence and photo-taking promulgated by the Nazi authorities.

Many of the photographs show Ostarbeiters in nice clothing and smiling cheerfully—a propagandistic tactic encouraged by the Nazis to reassure the captives’ loved ones. Initially, the Ministry of Propaganda staged photos in camps, but later Ostarbeiters were allowed to send photos taken in city studios or booths, albeit still censored; they complied, to ensure that their families received at least some communication. In an unfortunate personal context, I would note that, as a native of a region currently under Russian occupation, I frequently encounter similar portrayals of a “better” life, of “liberation” from Kyivan and Western “oppression,” in my daily communications with friends and relatives still living there. Thus, as is often the case in our field, this project holds significant personal resonance for its researcher.

Interpreting these photographs is complex. While they often show Ostarbeiters smiling and well dressed, they also reveal the grim realities of imprisonment, forced labor, and suffering. Outright negative reflections are relatively rare in the letters; more typically, they are encoded in metaphors, textual hints, and agreed-upon signs. Even more often, critical comments are found on the backs of photographs, which were sewn onto the letters, reducing the chances of being spotted by censors. For example, on the back of the following photograph, Halia Marchenko, who worked in Saint-Avold (in German-occupied France), has inscribed a song popular among Ostarbeiters, who longed for home and dreamed of returning from “damned captivity.”

“Коли вирвусь з проклятой неволі

Із Германієй скоро прощусь

В ешалоні в товарном вагоні

До вас мамо я скоро примчусь”.

“When I break free from damned captivity

I will soon say goodbye to Germany

In a special train, in a freight car

I will soon rush to you, mother.”

After the war, former Ostarbeiters were stigmatized as potential traitors and subjected to “filtration” to assess their loyalty, with those failing the test sent to prisons or the Gulag. Filtration exists also today for Ukrainians moving from the occupied territories to free Ukraine. Due to gendered perceptions of treachery, female Ostarbeiters faced particular abuse from Soviet soldiers: humiliation, rape, and other violence. Even those not imprisoned endured lasting health issues from dangerous work and unsafe abortions, along with barriers to education, careers, and family life. Victimized by both Nazi and Soviet regimes, their stories were often overlooked, and many remained silent for decades.

These people constituted what I consider to be a resilient subculture that emerged under extreme conditions. In Germany and the wider Reich, Ostarbeiters formed close-knit communities, communicating mainly with fellow Ukrainians due to language barriers and repression. Despite these hardships, they composed poems and songs and maintained a cultural life, with striking creative expressions, including photography. Unfortunately, once back in Soviet Ukraine, many Ostarbeiters found that their letters and photos had been destroyed by loved ones for fear of Soviet suspicions, which left their suffering undocumented and voices silenced. The condemnation of Ostarbeiters upon their return is akin to the challenge Ukrainians sometimes face today with those living under occupation, highlighting the need for careful consideration as to how we treat such individuals and territories post-liberation.

Initially, the Nazis’ promotion of the Ostarbeiter program was effective, but its impact diminished as truths emerged in letters and photos. While propaganda can create a measure of reality through repetition and sloganeering, oppressed individuals, like the Ostarbeiters, can critically assess and resist these messages. This ability to see through propaganda remains relevant today for Ukrainians under Russian occupation, and we should take care not to judge their behavior hastily, as few truly understand their hardships.

For Ukrainian studies to remain vibrant and relevant, both now and after the war, it’s important to communicate using familiar language, symbolism, and topics.

One of my goals is to resist overgeneralization, to develop an individualized approach and distinguish the various groups within Ostarbeiter society. Many Ostarbeiters were minors, as young as twelve or fourteen, when forced into slavery. Wartime displacement is traumatic for all, but children and teenagers face unique challenges due to their vulnerability, resulting in increased manipulation and abuse. Heavy labor and violence impacted these youngsters’ health and development, but in cases when conditions were more favorable, they often adapted quickly and returned home as changed individuals. Once more, this context has contemporary parallels—in issues of child labor and slavery in our global capitalist system, and I would be thrilled to see a student make this connection in a paper, applying their knowledge while exploring Ukraine’s past.

“I work at the factory on a lathe, the work is very easy. Night shifts are eleven hours long, day shifts are ten hours long. Somehow or other we get by.”

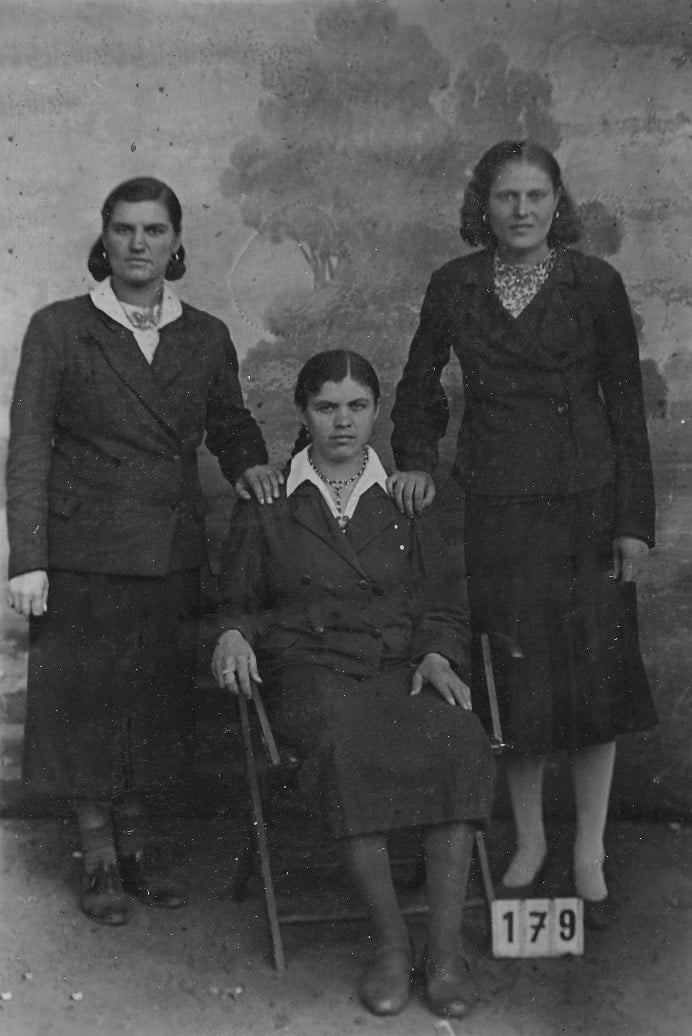

Not all of the Ostarbeiters’ photographs were purely propagandistic; some revealed harsh realities like poor living conditions and discriminatory badges, while others showed acts of resistance, such as preserving national identity through traditional attire or documenting forbidden activities like secret marriages. This photograph shows a scene familiar to a Slavic eye: a bride in traditional attire with her two bridesmaids. Though the letter lacks context, the image’s significance would be clear to the sender’s relatives. In this case, the photograph functions not only as proof of preserving one’s identity (and of the possibility of doing so, which the Nazis used to propagandize their alleged religious or ethnonational tolerance), but also as a coded message about a major event that had to be shared with the family.

In my research, I examine love and relationships (including same-sex ones) among Ostarbeiters, which occurred despite strict prohibitions. While many formed connections, women also faced sexual abuse, illegal prostitution, and pregnancies within the camps. Female Ostarbeiters often arrived pregnant or became so in Germany, facing forced abortions or having their newborns placed in poorly managed nurseries, or, in the case of “racially valuable” ones, taken by German families. This topic, too, invariably invokes contemporary worldwide parallels. Hanna Koval’s mention of her pregnancy reflects a sense of impending disaster.

“Olichka, you are so happy, but I am unhappy. Olichka, how is your health and how do you feel, because I feel bad. Will you have a son or daughter soon? Because I will have mine in six months. You are at least at home, but I am in a foreign land.”

During my exhibit at Harvard, I received numerous emails from descendants of Ostarbeiters who were deeply connected to the topic—many of whom had escaped Soviet repatriation and settled in the US, Canada, and Australia. I received valuable materials from these families, including photographs, letters, and diaries. This has inspired me to take the exhibit to other universities and community organizations, expanding my collection and bringing these stories and faces to light.

In their contributions to the effort to make Ukrainian studies a dynamic field encompassing both practical and theoretical aspects, many projects (I hope mine among them) can be of great relevance for our diverse audiences: viewers, listeners, students, and colleagues from various disciplines. To remain vibrant and relevant, both now and after the war, it’s important to communicate using familiar language, symbolism, and topics, and strategically promote what our culture and history have to offer on the international academic and cultural stage. This will be challenging—especially amid global instability and the long gloom on the humanities’ horizon—but it can be achieved through institutional collaboration and solidarity. Additionally, I believe that maintaining a balance between the striking uniqueness of our region and the universality of human experience will foster empathy and understanding beyond mere knowledge.

Alex Averbuch is a scholar, poet, and translator. He is currently an LSA collegiate fellow with the National Center for Institutional Diversity and an assistant professor of Ukrainian literature and culture in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Michigan. Previously he was a Killam postdoctoral fellow at the University of Alberta and a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University’s Davis Center and Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. His research explores propaganda, otherization, gender and sexuality, material culture, epistolarity, photography, theatricality and performance, translation, and creative writing. He is the author of three books of poetry and an array of over sixty selections of literary translations between Hebrew, Ukrainian, Russian, and English.